One major problem with the medical care of "obese" patients is that it's often based on what doctors think they know about obesity, rather than being truly evidence-based.

Certain maxims get taught about obesity, it influences medical procedures and protocols, and no one ever questions whether these beliefs are true or whether resulting protocols actually improve outcome.

Often, no one has even researched the question; they just assume outcomes are improved because everyone "knows" this way is best when dealing with fat patients.

More and more we are finding that these assumptions and protocols do not improve outcome, and in fact, sometimes actually worsen outcome.

Cesarean incision type in "obese" women is one of these issues.

Vertical Versus Transverse Incisions: What's Been Taught

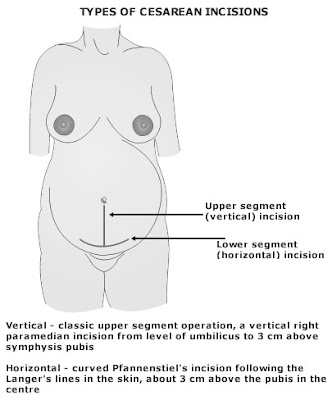

Doctors were taught for many years that a vertical (up-and-down) incision was better than a transverse (side-to-side) incision in "morbidly obese" and especially in "super-obese" patients.

They were told that a vertical incision was superior because the area under a fat woman's "apron" or "pannus" (the droopy belly flap overlap that some women have) was hot, moist, and prone to infection. Therefore, to lower the risk for infection, a vertical incision was made to avoid the area under the pannus.

I've seen this maxim repeated over and over in the medical literature throughout the years. And certainly, on my website I have the stories of a number of big moms who were given a vertical cesarean (low vertical or "classical"--i.e. stem to stern) and told it was "necessary" because of their obesity.

Yet to my surprise, until recently, few studies had actually EXAMINED whether a vertical incision actually improved outcomes or not in "obese" women.

Certainly it seems intuitive that avoiding the area under the belly might lower the risk for infection. But interestingly, several studies show the opposite ─ that vertical "up-down" incisions don't improve outcome at all ─ or actually worsen them. And they are certainly far more scarring and unsightly for the women involved.

The Studies That Examine Incisions in Women of Size

Interestingly, there were very few studies on this topic for a very long time; doctors were just taught without question that vertical incisions would reduce the risk of infection and speed up operating time.

Over time, many doctors began using low transverse incisions on women with moderate obesity, and eventually some began expanding their use into women with more "severe" obesity as well. As a result, many women of size did have low transverse incisions, while other doctors kept using vertical incisions on "supersized" women. Yet few people studied which was superior until about 10 years ago.

In 2001, D'Heureux-Jones et al. presented a paper on a small study that compared different combinations of incisions in obese patients. They found that the low transverse (skin and uterine) incision was the best incision for obese women because it was faster and had less morbidity associated with it. Vertical abdominal incisions had the highest blood loss rate. They concluded that a low transverse incision was advantageous "because it improves speed of operation, blood loss, and rate of complications" in obese patients.

In 2003, Wall et al. did a larger study examining this question. They examined the records of 239 women with a BMI of 35 or more. The wound complication rate was 12.1%, or nearly 1 in 8 women of this size. They found that vertical incisions were associated with twelve times the risk for wound complications.

Alanis 2010 found that vertical incisions had greater blood loss in super-obese women (BMI 50+), and they did not improve outcome. Contrary to expectations, they also found that vertical incisions also had increased operative time. To improve outcome in this group, they suggested forgoing surgical drains and promoting low transverse incisions.

Bell et al. (2011) studied 424 women with BMI greater than 35 who had a cesarean between 2004 and 2006, including 41 who had a vertical incision. After adjusting for confounders, the study found that vertical skin incisions were not associated with higher rates of wound complications or blood loss.

However, if the full text of the study is examined, there actually were quite a bit more wound complications (14.6% in the vertical incision group vs. 7.6% in the low transverse group) and blood transfusions (9.8% in the vertical group vs. 1.6% in the low transverse group). These simply did not rise to statistical significance after controlling for confounders. The adjusted odds ratios were 1.91 for wound complication and 2.78 for blood transfusion with vertical incisions, but the confidence intervals were very wide and crossed 1.0, so the results could not be said to be statistically significant. However, the trend towards more complications with a vertical skin incision was very clear. With more subjects in the vertical incision arm, these differences might have risen to statistical significance.

Other Problems with Vertical Incisions

In addition to these concerns, research also indicates that vertical incisions tend to be less strong than transverse incisions, and more prone to dehiscence (coming apart) during recovery.

Women with classical incisions also tend to experience more complications, including post-operative pulmonary issues, more pain, blood transfusions, infections, and more admissions to intensive care units afterwards.

Most importantly, vertical skin incisions often meant vertical incisions in the uterus below. For example, both Bell et al. (2011) and Alanis 2010 found increased rates of vertical/classical incisions in the uterus when vertical skin incisions were used. Bell found that when doctors used a vertical skin incision on obese women, 66% (two-thirds!) went on to use a classical vertical uterine incision too.

A classical vertical uterine incision places these women at strong risk for future complications, particularly uterine rupture, should any more pregnancies occur.

Bakhshi 2010 found that women with a prior classical cesarean had longer hospitalizations, longer operative times, and more admissions to intensive care units in a subsequent pregnancy. Most importantly, they had a greatly increased incidence of scar separations in their pregnancies compared to women with a prior low transverse uterine incision (2.46% vs. 0.27%).

As the authors of Alanis 2010 say in their study:

Although some studies have found that outcomes were statistically similar between vertical incisions and low transverse incisions (usually because of too few partcipants), none have shown better outcome with vertical incisions.

Given the lack of data showing vertical incisions to be superior, not to mention the associated post-operative and future risks with them, the question is why these vertical incisions continue to be used in women of size.

Cosmetic Considerations

Furthermore, it must be pointed out that vertical incisions can be very scarring emotionally and physically.

A low transverse incision is not usually terribly visible long after it's healed. Although all scars are annoying to deal with and can have long-term emotional impact, a transverse incision tends to have less long-term psychological impact because it's further down on the abdomen and not nearly as obviously visible.

Although still traumatic to many women, a transverse scar is less mutilating to a woman's general sense of self.

On the other hand, a vertical incision often leaves a line of separated-looking tissue underneath, as demonstrated in the following pictures.

Some doctors have the attitude that it "doesn't matter" if an incision is vertical in a fat woman. Some have even told fat women that they gave them a vertical incision because "it's not like you're going to be wearing a bikini."

This is an unjust, callous, and unreasonable reason for imposing a vertical incision. Whether or not they ever wear a bikini is irrelevant to the discussion. It matters to the woman and her partner.

Women with vertical incisions often complain that their incision "looks like a giant butt" on their frontside, and find it unsexy and humiliating for partners to see. It also can create problems under clothes and limit what fabrics and styles people choose to wear.

Although it's "just" cosmetic, a vertical skin incision can have profound impact on a woman's body esteem. Unless there is a better outcome associated with it, it simply should not be used routinely in women of size.

Conclusion

Although the practice of doing a vertical or classical incision on "very obese" women has declined somewhat over the years, it is still done at times. Some doctors do it because they still believe that it's "safer" and less prone to infection in women of size; some do it because it can be technically and physically difficult to do low transverse incisions on women with a larger belly.

While it is important to acknowledge that it is harder to do cesareans on very fat women, and there can be occasions where alternate incisions become necessary, most of the time low transverse incisions are very do-able in fat women, even "morbidly obese" and "super obese" women.

As the authors of Alanis 2010 say in their study:

Once doctors actually started looking into the question, research showed that it is NOT necessary to do vertical incisions in fat women, even "massively obese" women. Outcomes are no better or are actually poorer when vertical incisions are used, despite what many doctors have been taught for so long.

The tendency towards greater blood loss, more wound complications, poorer cosmetic outcomes, more classical uterine incisions (and associated negative impact on future pregnancies) all suggest that vertical incisions should be avoided in most obese women.

Low transverse incisions have been used successfully even in extremely obese women (BMI of 88) in case reports found in the medical literature. Unless there are other complicating factors to consider, a vertical skin incision should NOT be used routinely in fat women.

Vertical Incisions vs. Low Transverse Incisions in Women of Size

Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Nov;102(5 Pt 1):952-6. Vertical skin incisions and wound complications in the obese parturient. Wall PD, Deucy EE, Glantz JC, Pressman EK. PMID: 14672469

Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Oct;100(4):633-7. Maternal and perinatal morbidity associated with classic and inverted T cesarean incisions. Patterson LS, O'Connell CM, Baskett TF. PMID: 12383525

Certain maxims get taught about obesity, it influences medical procedures and protocols, and no one ever questions whether these beliefs are true or whether resulting protocols actually improve outcome.

Often, no one has even researched the question; they just assume outcomes are improved because everyone "knows" this way is best when dealing with fat patients.

More and more we are finding that these assumptions and protocols do not improve outcome, and in fact, sometimes actually worsen outcome.

Cesarean incision type in "obese" women is one of these issues.

Vertical Versus Transverse Incisions: What's Been Taught

Doctors were taught for many years that a vertical (up-and-down) incision was better than a transverse (side-to-side) incision in "morbidly obese" and especially in "super-obese" patients.

They were told that a vertical incision was superior because the area under a fat woman's "apron" or "pannus" (the droopy belly flap overlap that some women have) was hot, moist, and prone to infection. Therefore, to lower the risk for infection, a vertical incision was made to avoid the area under the pannus.

I've seen this maxim repeated over and over in the medical literature throughout the years. And certainly, on my website I have the stories of a number of big moms who were given a vertical cesarean (low vertical or "classical"--i.e. stem to stern) and told it was "necessary" because of their obesity.

Yet to my surprise, until recently, few studies had actually EXAMINED whether a vertical incision actually improved outcomes or not in "obese" women.

Certainly it seems intuitive that avoiding the area under the belly might lower the risk for infection. But interestingly, several studies show the opposite ─ that vertical "up-down" incisions don't improve outcome at all ─ or actually worsen them. And they are certainly far more scarring and unsightly for the women involved.

The Studies That Examine Incisions in Women of Size

Interestingly, there were very few studies on this topic for a very long time; doctors were just taught without question that vertical incisions would reduce the risk of infection and speed up operating time.

Over time, many doctors began using low transverse incisions on women with moderate obesity, and eventually some began expanding their use into women with more "severe" obesity as well. As a result, many women of size did have low transverse incisions, while other doctors kept using vertical incisions on "supersized" women. Yet few people studied which was superior until about 10 years ago.

In 2001, D'Heureux-Jones et al. presented a paper on a small study that compared different combinations of incisions in obese patients. They found that the low transverse (skin and uterine) incision was the best incision for obese women because it was faster and had less morbidity associated with it. Vertical abdominal incisions had the highest blood loss rate. They concluded that a low transverse incision was advantageous "because it improves speed of operation, blood loss, and rate of complications" in obese patients.

In 2003, Wall et al. did a larger study examining this question. They examined the records of 239 women with a BMI of 35 or more. The wound complication rate was 12.1%, or nearly 1 in 8 women of this size. They found that vertical incisions were associated with twelve times the risk for wound complications.

Alanis 2010 found that vertical incisions had greater blood loss in super-obese women (BMI 50+), and they did not improve outcome. Contrary to expectations, they also found that vertical incisions also had increased operative time. To improve outcome in this group, they suggested forgoing surgical drains and promoting low transverse incisions.

Bell et al. (2011) studied 424 women with BMI greater than 35 who had a cesarean between 2004 and 2006, including 41 who had a vertical incision. After adjusting for confounders, the study found that vertical skin incisions were not associated with higher rates of wound complications or blood loss.

However, if the full text of the study is examined, there actually were quite a bit more wound complications (14.6% in the vertical incision group vs. 7.6% in the low transverse group) and blood transfusions (9.8% in the vertical group vs. 1.6% in the low transverse group). These simply did not rise to statistical significance after controlling for confounders. The adjusted odds ratios were 1.91 for wound complication and 2.78 for blood transfusion with vertical incisions, but the confidence intervals were very wide and crossed 1.0, so the results could not be said to be statistically significant. However, the trend towards more complications with a vertical skin incision was very clear. With more subjects in the vertical incision arm, these differences might have risen to statistical significance.

Other Problems with Vertical Incisions

In addition to these concerns, research also indicates that vertical incisions tend to be less strong than transverse incisions, and more prone to dehiscence (coming apart) during recovery.

Women with classical incisions also tend to experience more complications, including post-operative pulmonary issues, more pain, blood transfusions, infections, and more admissions to intensive care units afterwards.

Most importantly, vertical skin incisions often meant vertical incisions in the uterus below. For example, both Bell et al. (2011) and Alanis 2010 found increased rates of vertical/classical incisions in the uterus when vertical skin incisions were used. Bell found that when doctors used a vertical skin incision on obese women, 66% (two-thirds!) went on to use a classical vertical uterine incision too.

A classical vertical uterine incision places these women at strong risk for future complications, particularly uterine rupture, should any more pregnancies occur.

Bakhshi 2010 found that women with a prior classical cesarean had longer hospitalizations, longer operative times, and more admissions to intensive care units in a subsequent pregnancy. Most importantly, they had a greatly increased incidence of scar separations in their pregnancies compared to women with a prior low transverse uterine incision (2.46% vs. 0.27%).

As the authors of Alanis 2010 say in their study:

Our results also support the use of Pfannenstiel incisions in obese patients with a large panniculus and contradict classic teaching by veteran surgeons and obstetrical texts. It has been written that transverse abdominal incisions made under the pannicular fold exist in “a warm, moist, anaerobic environment associated with impaired bacteriostasis . . .[that] promotes the proliferation of numerous microorganisms, producing a veritable bacteriologic cesspool.” However, we are unable to locate any evidence to support this popular conclusion...It is notable that the authors could not find any evidence in the research to support the common teaching about use of vertical incisions to prevent infections in obese women. Again, this shows that many maxims that are taught about obesity and pregnancy are not necessarily supported by evidence.

Transverse abdominal incisions are less painful and allow for earlier mobilization and decreased pulmonary complications. Furthermore, vertical abdominal incisions were associated with vertical hysterotomy in our study, usually a result of inadequate access to the lower uterine segment. When the incision extends into the contractile portion of the uterus, a vertical hysterotomy has a profound impact on future pregnancy. Therefore, it is important to incorporate practices, like transverse abdominal incisions, that facilitate low uterine incisions.

Although some studies have found that outcomes were statistically similar between vertical incisions and low transverse incisions (usually because of too few partcipants), none have shown better outcome with vertical incisions.

Given the lack of data showing vertical incisions to be superior, not to mention the associated post-operative and future risks with them, the question is why these vertical incisions continue to be used in women of size.

Cosmetic Considerations

Furthermore, it must be pointed out that vertical incisions can be very scarring emotionally and physically.

|

| Long-term Results from Low Transverse Incision in a woman of size photo from website reader |

A low transverse incision is not usually terribly visible long after it's healed. Although all scars are annoying to deal with and can have long-term emotional impact, a transverse incision tends to have less long-term psychological impact because it's further down on the abdomen and not nearly as obviously visible.

Although still traumatic to many women, a transverse scar is less mutilating to a woman's general sense of self.

On the other hand, a vertical incision often leaves a line of separated-looking tissue underneath, as demonstrated in the following pictures.

|

| Recent Vertical Incision on a Woman of Size From pregnancy.about.com |

|

| Long-Term Results of a Vertical Incision on a Woman of Size photo from blog reader |

|

| Long-Term Results of Vertical Incision photo from website reader |

Some doctors have the attitude that it "doesn't matter" if an incision is vertical in a fat woman. Some have even told fat women that they gave them a vertical incision because "it's not like you're going to be wearing a bikini."

This is an unjust, callous, and unreasonable reason for imposing a vertical incision. Whether or not they ever wear a bikini is irrelevant to the discussion. It matters to the woman and her partner.

|

| Botched Vertical CS Incision from makemeheal.com |

Women with vertical incisions often complain that their incision "looks like a giant butt" on their frontside, and find it unsexy and humiliating for partners to see. It also can create problems under clothes and limit what fabrics and styles people choose to wear.

Although it's "just" cosmetic, a vertical skin incision can have profound impact on a woman's body esteem. Unless there is a better outcome associated with it, it simply should not be used routinely in women of size.

Conclusion

Although the practice of doing a vertical or classical incision on "very obese" women has declined somewhat over the years, it is still done at times. Some doctors do it because they still believe that it's "safer" and less prone to infection in women of size; some do it because it can be technically and physically difficult to do low transverse incisions on women with a larger belly.

While it is important to acknowledge that it is harder to do cesareans on very fat women, and there can be occasions where alternate incisions become necessary, most of the time low transverse incisions are very do-able in fat women, even "morbidly obese" and "super obese" women.

As the authors of Alanis 2010 say in their study:

Our results also support the use of Pfannenstiel incisions in obese patients with a large panniculus and contradict classic teaching by veteran surgeons and obstetrical texts...Doctors must start questioning the conventional wisdom that they are taught about what's best for "obese" people. They need to find out if this teaching is actually based on real research, and if so, whether the research has adequately controlled for confounding factors.

Although a Pfannenstiel incision can be challenging in obese patients with an overhanging panniculus, it is usually feasible in all but the most obese women.

Once doctors actually started looking into the question, research showed that it is NOT necessary to do vertical incisions in fat women, even "massively obese" women. Outcomes are no better or are actually poorer when vertical incisions are used, despite what many doctors have been taught for so long.

The tendency towards greater blood loss, more wound complications, poorer cosmetic outcomes, more classical uterine incisions (and associated negative impact on future pregnancies) all suggest that vertical incisions should be avoided in most obese women.

Low transverse incisions have been used successfully even in extremely obese women (BMI of 88) in case reports found in the medical literature. Unless there are other complicating factors to consider, a vertical skin incision should NOT be used routinely in fat women.

References

Vertical Incisions vs. Low Transverse Incisions in Women of Size

OBJECTIVE: To examine the relationship between the type of skin incision and postoperative wound complications in an obese population.

METHODS: A hospital-based perinatal database was used to identify women with a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 35 undergoing their first cesarean delivery. Hospital and outpatient medical records were reviewed for the following variables: age, insurance status, BMI, gestational age at delivery, birth weight, smoking history, prior abdominal surgery, existing comorbidities, preoperative hematocrit, chorioamnionitis, duration of labor and membrane rupture, dilation at time of cesarean delivery, type of skinand uterine incision, estimated blood loss, operative time, antibiotic prophylaxis, use of subcutaneous drains or sutures, endometritis, and length of stay. The primary outcome variable was any wound complication requiring opening the incision. Multiple logistic regression analysis was completed to determine which of these factors contributed to the incidence of wound complications.

RESULTS: From 1994 to 2000, 239 women with a BMI greater than 35 undergoing a primary cesarean delivery were identified. The overall incidence of wound complications in this group of severely obese patients was 12.1%. Factors associated with wound complications included vertical skin incisions (odds ratio [OR] 12.4, P less than .001) and endometritis (OR 3.4, P = .03). A high preoperative hematocrit was protective (OR .87, P = .03). No other factors were found to impact wound complications.

CONCLUSION: Primary cesarean delivery in the severely obese parturient has a high incidence of wound complications. Our data indicate that a vertical skin incision is associated with a higher rate of wound complications than a transverse incision.

D’Heureux-Jones AM. Incision choice for cesarean celivery in obese patients: experience in a university hospital. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2001 Apr;97(4 Suppl 1):S62-S63. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0029784401012959

Objective: Cesarean deliveries in obese patients are surgically difficult and associated with a higher incidence of complications. The choices of skin or uterine incision are subjective. Our aim was to determine the impact of different incisions on the speed of the operation and the intraoperative and postoperative morbidity in obese patients.Complications of cesarean delivery in the massively obese parturient. Alanis MC, Villers MS, Law TL, Steadman EM, Robinson CJ. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Sep;203(3):271.31-7. PMID: 20678746

Methods: We conducted a 14-month retrospective review of all primary singleton cesarean deliveries performed at our institution. The abdominal (vertical: V, or Pfannenstiel: P) and uterine incision (low transverse: L, or classical: C) were evaluated by one-way and two-way ANOVA for their impact on the time of delivery (skin–baby) based on maternal weight in obese (>200 lb) versus nonobese women. Measures of intraoperative and postoperative morbidity included EBL, wound infections, and metritis.

Results: Seventy-one patients were subjects of this study. Forty-five patients (63%) met criteria for obesity (265.1 ± 8.4 lbs), significantly different from nonobese patients (156.5 ± 4.1 lbs). PL was the most frequent association both in the obese (64%, n = 29) and nonobese (88%, n = 23), with an average skin–baby time of 9.4 ± 0.8 minutes and 9.9 ± 1.1minutes, respectively (P < 0.05). In both obese and nonobese patients, a C was associated with a higher rate of prematurity and NICU admission. When a C was performed, the time was longer if the patient was obese (16.4 ± 2.8 min) versus nonobese (9.07 + 1.2 min), P = 0.03). Skin incisions did not affect the speed of delivery. In obese patients, VL had the highest EBL (1,167 ± 3.57 cc) and PL the lowest (1,075 ± 5.1cc, P = 0.02), both increased compared with nonobese patients with similar incisions. Metritis, but not wound infection, was more frequent in obese patients (20%) versus nonobese patients (3%), irrespective of the incision type. Length of stay was not affected either by obesity or by incision type.

Conclusions: The combination of P and L is preferred for cesarean delivery in both obese and nonobese patients. For obese patients, PL is further advantageous because it improves speed of operation, blood loss, and rate of complications.

OBJECTIVE: The objective of the study was to determine predictors of cesarean delivery morbidity associated with massive obesity.Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011 Jan;154(1):16-9. Epub 2010 Sep 15. Abdominal surgical incisions and perioperative morbidity among morbidly obese women undergoing cesarean delivery. Bell J, Bell S, Vahratian A, Awonuga AO. PMID: 20832161

STUDY DESIGN: This was an institutional review board-approved retrospective study of massively obese women (body mass index, greater than/=50 kg/m(2)) undergoing cesarean delivery. Bivariable and multivariable analyses were used to assess the strength of association between wound complication and various predictors.

RESULTS: Fifty-eight of 194 patients (30%) had a wound complication. Most (90%) were wound disruptions, and 86% were diagnosed after hospital discharge (median postoperative day, 8.5; interquartile range, 6-12). Subcutaneous drains and smoking, but not labor or ruptured membranes, were independently associated with wound complication after controlling for various confounders. Vertical abdominal incisions were associated with increased operative time, blood loss, and vertical hysterotomy.

CONCLUSION: Women with a BMI 50 kg/m(2) or greater have a much greater risk for cesarean wound complications than previously reported. Avoidance of subcutaneous drains and increased use of transverse abdominal wall incisions should be considered in massively obese parturients to reduce operative morbidity.

OBJECTIVE: To test the hypothesis that there is no difference in perioperative morbidity and the type of uterine incisions between vertical skin incisions (VSI) and low transverse skin incisions (LTSI) at the time of cesarean delivery in morbidly obese women.Risks of Classical Cesareans

STUDY DESIGN: Retrospective cohort study of morbidly obese women (BMI greater than 35 kg/m(2)) who underwent cesarean delivery between June 2004 and December 2006.

RESULTS: During the study, 424 morbidly obese women underwent cesarean section. Patients with VSI were older (31.0 ± 6.2 years vs. 26.7 ± 5.8 years), heavier (48.2 ± 9.1 kg/m(2) vs. 41.7 ± 6.7 kg/m(2)), and more likely to have a classical than a low transverse uterine incision (65.9% vs. 7.3%), p less than 0.001. After controlling for confounders, women with VSI did not have an increase in perioperative morbidity, but underwent more vertical uterine incisions (adjusted odds ratio = 18.49, 95% CI: 6.44, 53.07).

CONCLUSION: VSI and LTSI are safe in morbidly obese patients undergoing cesarean section, but there is a tendency for increased vertical uterine incisions in those who underwent VSI.

Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Oct;100(4):633-7. Maternal and perinatal morbidity associated with classic and inverted T cesarean incisions. Patterson LS, O'Connell CM, Baskett TF. PMID: 12383525

OBJECTIVE: To estimate the maternal and perinatal morbidity associated with cesarean delivery involving the upper uterine segment compared with that of low transverse cesarean delivery. METHODS: A 19-year review of a perinatal database and the relevant charts was used to determine the maternal and perinatal morbidity associated with low transverse cesarean, classic cesarean, and inverted "T" cesarean deliveries. RESULTS:Over the 19 years, 1980-1998, there were 19,726 cesarean deliveries: low transverse cesarean, 19,422 (98.5%); classiccesarean, 221 (1.1%); and inverted T cesarean, 83 (0.4%). As a proportion of all cesarean deliveries, the rates of low transverse cesarean and classic cesarean have remained stable, whereas the rate of inverted T cesarean has risen from 0.2% to 0.9%. Maternal morbidity (puerperal infection, blood transfusion, hysterectomy, intensive care unit admission, death) and perinatal morbidity (stillborn fetus, neonatal death, 5 minute Apgar less than 7, intensive care) were significantly higher in classic cesarean compared to low transverse cesarean. Some maternal morbidity (puerperal infection, blood transfusion) and perinatal morbidity (5 minute Apgar less than 7, intensive care) were also significantly higher for inverted T cesarean compared to low transverse cesarean. CONCLUSION: Classic cesarean section has a higher maternal and perinatal morbidity than inverted T cesarean and much higher than low transverse cesarean. There is no increased maternal or perinatal morbidity if an attempted low transverse incision has to be converted to an inverted "T" incision compared to performing a classic cesarean section.Am J Perinatol. 2010 Nov;27(10):791-6. Epub 2010 May 10. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of repeat cesarean delivery in women with a prior classical versus low transverse uterine incision. Bakhshi T, et al. PMID: 20458666

We compared maternal and neonatal outcomes following repeat cesarean delivery (CD) of women with a prior classical CD with those with a prior low transverse CD. The Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network Cesarean Delivery Registry was used to identify women with one previous CD who underwent an elective repeat CD prior to the onset of labor at ≥36 weeks. Outcomes were compared between women with a previous classical CD and those with a prior low transverse CD. Of the 7936 women who met study criteria, 122 had a prior classical CD. Women with a prior classical CD had a higher rate of classical uterine incision at repeat CD (12.73% versus 0.59%; P less than 0.001), had longer total operative time and hospital stay, and had higher intensive care unit admission. Uterine dehiscence was more frequent in women with a prior classical CD (2.46% versus 0.27%, odds ratio 9.35, 95% confidence interval 1.76 to 31.93). After adjusting for confounding factors, there were no statistical differences in major maternal or neonatal morbidities between groups. Uterine dehiscence was present at repeat CD in 2.46% of women with a prior classical CD. However, major maternal morbidities were similar to those with a prior low transverse CD.