|

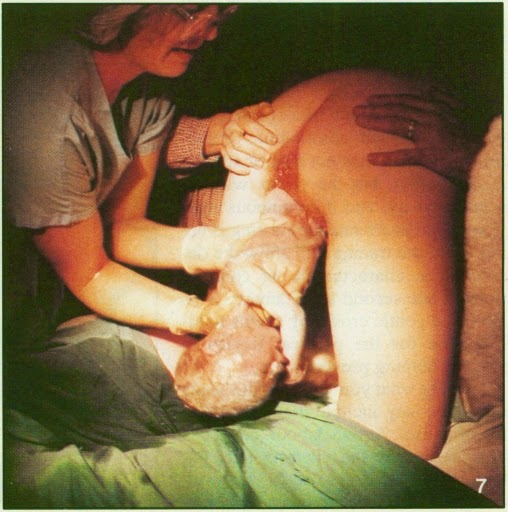

| The view most women have during birth in most hospitals |

Specifically, we are most interested in "alternative" birth positions, ones that are under-utilized in the hospital.

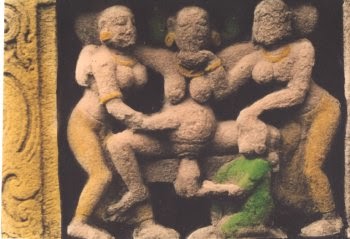

Part One of this series discussed Historical and Traditional Birth Positions because in ancient times and in traditional cultures, birth positions were typically more varied. Upright positions were common, although all positions can be found in ancient artwork.

In contrast, in hospitals today, most women give birth in very limited positions, usually one of three ─ either completely lying back ("lithotomy," "supine," or "dorsal recumbent"), partially reclined ("Semi-Fowlers" or "semi-recumbent"), or semi-sitting with knees widely abducted and pulled back and the chest and head rounded forward ("C" position).

Uniformity of Positions in the Hospital

Sadly, while care providers pay lip service to mobility in labor, their actions speak differently. Most women in labor are encouraged to lay back in labor in either a slightly reclined or semi-sitting position. Laying on the side is well-accepted in most hospitals but is often under-utilized.

Although progress has been made and some providers now "allow" women to labor or push in any position, their tune often changes when it's time for the baby to actually come out. At that point, most women are required (or so strongly pressured that it's basically a requirement) to lie back or to use a semi-sitting, knees-back position.

Pervasive Cultural Image of Birth

Sadly, this historical precedent for reclining birth became programmed into our media images of birth until it has become our pervasive cultural image of birth. This is one of the strongest influences on maternal positioning today.

In movies and on TV, women almost always give birth in the prone or semi-sitting position, probably because it's all the writers and viewers know from their own lives and the lives of their friends and relatives.

Years ago, I worked on a play which had a birth scene in it from the pioneer days. The director had the woman on her back, knees flexed and back, like the usual media images of a hospital birth. I pointed out that most women in that era didn't birth like that and provided documentation. The director incorporated my input into rehearsal, but decided that nobody in the audience would understand because she “didn't look like she was giving birth.” We found a compromise (the actress "labored" in a semi-recumbent position but rose to a supported squat for the actual "birth") but it was frustrating that the recumbent position is so ingrained into our cultural expectations that anything else was seen as confusing to the audience. That is difficult to overcome.

As the pioneering film, Laboring Under An Illusion: Mass Media Childbirth vs. The Real Thing by anthropologist Vicki Elson points out, this pervasive culture image makes it difficult for women (and care providers) to envision any other position for birth, and often unwilling to even try it, even when equipment for other positions is provided and they are encouraged to be mobile.

Thus this position has become a self-perpetuating custom. But it doesn't have to stay that way!

Ease of Interventions

One practical barrier to alternative positions is that the recumbent positions make some common labor interventions easier.

Birthing women are dealing with a hospital medical culture that has a very high rate of labor interventions (like induction and augmentation) that necessitate extremely close monitoring of fetal and maternal well-being. Procedures like fetal monitoring, IV fluids, and vaginal exams are easier when the mother is reclining. In addition, labor interventions that strengthen contractions raise the need for epidurals, which then often results in the mother laboring in a reclining position.

All of these things combine to create a powerful hospital culture that encourages a reclining, passive position for labor and birth. The mother is the passive patient that is having interventions done to her, the care providers are the active ones who are directing the labor. Even the language reinforces this; the doctor "delivers" the baby, rather than the woman "gives birth" to her child. As one researcher states:

However, the reality is that an intervention-free childbirth is uncommon in the hospital, sometimes interventions are truly medically necessary, and many women choose interventions like epidurals or inductions. Although more intervention-free childbirth is a worthy goal, greater variety in birthing positions does not depend on it. Alternative birth positions can still be used in women with interventions.

For example, although outcomes are not improved with the use of EFM, most hospitals feel they still have to use it as a defense against lawsuits. But while it can be more challenging to use EFM in "alternative" positions, it can and has been done.

EFM, induction, augmentation, IV fluids, and epidurals do not have to be a barrier to alternative positioning. It just requires being a little more creative. (A doula can be very helpful in this process.)

Care Provider Comfort and Convenience

Conclusion

The vast majority of women in U.S. hospitals give birth in reclining or semi-sitting positions. This is not because their care providers are mean or wish them harm, it is because these positions have become rigidly ingrained into medical training, hospital culture, and popular culture. But it doesn't have to stay that way.

Although reclining positions are still seen frequently in many European and Australian hospitals too, alternative positions are more encouraged and accepted in these areas. In fact, most recent research on "alternative" positions is being done in Europe or Australia.

Look at some of the birthing room equipment available in the British labor ward video and the German birthing room picture above. Why isn't this standard in most U.S. hospitals?

[To be fair, some of it IS in some U.S. hospitals. But often it's only available on request or in a special room, not just a routine part of every birthing room. And too often, it's only for labor, not for the actual birth.]

Although research on utilization of birthing positions is sparse, it suggests that the pervasive image of birth in the media and established hospital culture subtly influence women towards reclining positions. It also suggests that certain models of care (such as birth clinics and births attended by midwives) tend to utilize higher levels of alternative positions for birth.

Of course, it's not just midwives who attend these births; there are some absolutely awesome OBs and family docs out there too who are attending births in all kinds of positions. The title of the birth attendant is less important than their philosophy.

Women are more likely to find support for using alternative positions if their care provider believes strongly in physiologic birth, is supportive of natural childbirth, and has low intervention rates in labor.

Even if you are planning on having an epidural or are being induced, having a provider comfortable with natural childbirth increases your chances of using alternative positions despite these interventions.

To find out how supportive your care provider truly is of alternative positions, ask them to estimate what percentage of the births they've attended have been in non-recumbent positions. (Not labored in, but actually pushed the baby out in. Remember, many attendants are fine with mobility in labor but require women to be sitting or reclining for the actual "delivery" of the baby. You are looking for the ones that have experience and comfort with alternative positions for the actual birth too.)

It is mostly tradition, training, and comfort levels that keep reclining positions as the standard of care in many hospitals. But with education and flexibility, caregivers in the hospital can become more open to other positions and accommodate them in a way that respects the mother's needs as well as their own needs.

Hospital caregivers CAN learn to safely attend births in alternative positions, and research suggests that doing so may help improve some birth outcomes, as well as helping labor to be less painful for the mother.

It's about time these "alternative" positions became more widespread in medical schools, hospitals, and birthing clinics all around the world.

Uniformity of Positions in the Hospital

|

| Most women in the hospital give birth like this |

Although progress has been made and some providers now "allow" women to labor or push in any position, their tune often changes when it's time for the baby to actually come out. At that point, most women are required (or so strongly pressured that it's basically a requirement) to lie back or to use a semi-sitting, knees-back position.

As we mentioned in Part One of the series, one survey of U.S. birthing women as recently as 2005 reported that 92% of the women gave birth in either semi-reclining/reclining or semi-sitting positions.

If all those women find these positions comfortable and truly want to give birth in them, that's no problem. However, many women report wanting to use other positions and being actively discouraged or even forbidden from using them. [I know I was actively discouraged from other positions in one of my hospital births.]

This practice is so widespread that many medical students never see a birth in any position other than lying back or semi-sitting. One medical student reported in 2013 (my emphasis):

These positions are less than ideal because they:

These are not ideal circumstances for a safer and easier birth. Despite this, it has been very difficult to get alternative positions accepted into regular practice in many hospitals.

Barriers to Alternative Positions

There are many cultural and technological factors that influence birth position. But if "alternative" positions used to be the norm, why has cultural practice changed so markedly? Frankly, there are a number of factors at work here, including:

If all those women find these positions comfortable and truly want to give birth in them, that's no problem. However, many women report wanting to use other positions and being actively discouraged or even forbidden from using them. [I know I was actively discouraged from other positions in one of my hospital births.]

This practice is so widespread that many medical students never see a birth in any position other than lying back or semi-sitting. One medical student reported in 2013 (my emphasis):

I finished my Obstetrics and Gynecology clerkship 5 weeks ago. I did my clerkship at a large, and rather posh, private hospital that is affiliated with my medical school. There are some great doctors there, but I was sometimes aghast at the rather aggressive approach to delivery that many took. The cesarean section rate for the last year was 47%, well above the national average of 33%, and most labors were artificially augmented. I did not witness a single VBAC (Vaginal Birth After Cesarean), and was told that only one of the house attendings would perform them.Although there are hospital care providers out there that are comfortable attending births in alternate positions, the vast majority of hospital births, even today, are in the un-physiological laying back or semi-sitting positions.

On the first day of my clerkship, I asked the clerkship director if women delivered in a variety of positions or if they were restricted to delivering in lithotomy (what many today think of as the “traditional” birthing position with the mother on her back with her feet in stirrups). The director seems to be a rather progressive woman...and she gave me a rather knowing look and said “I know what you’re getting at, but unfortunately everyone here delivers lying down”.

Indeed, as I went through my rotation, all the vaginal deliveries I saw were done in the semi-reclined position that is common in western hospitals.

These positions are less than ideal because they:

- make the mother work against gravity

- decrease the pelvic outlet by restricting free movement of the sacrum and tailbone during birth

- compress the main artery that brings blood to the uterus, causing a tendency towards low oxygen to the baby, fetal distress, and maternal "supine hypotension"

These are not ideal circumstances for a safer and easier birth. Despite this, it has been very difficult to get alternative positions accepted into regular practice in many hospitals.

Barriers to Alternative Positions

There are many cultural and technological factors that influence birth position. But if "alternative" positions used to be the norm, why has cultural practice changed so markedly? Frankly, there are a number of factors at work here, including:

- Recent Historical Precedent

- Pervasive Cultural Image of Birth

- Ease of Interventions

- Care Provider Comfort and Convenience

- Care Provider Training

Let's take a closer look at each one of these.

Historical Precedent

Historical medical factors are central to why women no longer birth in upright positions most of the time.

These factors are no longer relevant, yet the tradition of reclining birth became so strongly ingrained that this position is considered the norm for childbirth even now.

These factors are no longer relevant, yet the tradition of reclining birth became so strongly ingrained that this position is considered the norm for childbirth even now.

|

| Hospital birth in the old days |

When birth came into the hospital, women usually gave birth lying down because they were heavily drugged. Many were even tied down during contractions. As a result, women were usually flat on their backs with their legs strapped into stirrups because they could not hold their legs up themselves. Doctors often had to use forceps to help the baby negotiate its way out, and they needed the women in a position that gave them maximum access to the perineum.

|

| Modern hospital birth, still ready for the episiotomy |

Furthermore, because of the forceps and the heavy-duty drugs given to laboring women, an episiotomy to speed up the birth was considered mandatory in many hospitals, and this was easier in a prone or lying-back position. Sadly, ease of episiotomy is still one of the reasons doctors like the lithotomy or semi-sitting position today, as the modern picture above shows.

Most women these days are not so drugged that they need to be prone in bed, forceps have mostly fallen out of use, and research has shown over and over how harmful routine episiotomies are. There is little need for women to be prone in bed for birth anymore, yet the tradition persists.

Although historically it is understandable that this tradition of lying/sitting for birth developed in the highly-technological and interventive hospital births of the mid-20th century, there really is no good reason to insist on these positions for all births anymore.

Sadly, this historical precedent for reclining birth became programmed into our media images of birth until it has become our pervasive cultural image of birth. This is one of the strongest influences on maternal positioning today.

In movies and on TV, women almost always give birth in the prone or semi-sitting position, probably because it's all the writers and viewers know from their own lives and the lives of their friends and relatives.

Years ago, I worked on a play which had a birth scene in it from the pioneer days. The director had the woman on her back, knees flexed and back, like the usual media images of a hospital birth. I pointed out that most women in that era didn't birth like that and provided documentation. The director incorporated my input into rehearsal, but decided that nobody in the audience would understand because she “didn't look like she was giving birth.” We found a compromise (the actress "labored" in a semi-recumbent position but rose to a supported squat for the actual "birth") but it was frustrating that the recumbent position is so ingrained into our cultural expectations that anything else was seen as confusing to the audience. That is difficult to overcome.

As the pioneering film, Laboring Under An Illusion: Mass Media Childbirth vs. The Real Thing by anthropologist Vicki Elson points out, this pervasive culture image makes it difficult for women (and care providers) to envision any other position for birth, and often unwilling to even try it, even when equipment for other positions is provided and they are encouraged to be mobile.

Ease of Interventions

|

| Electronic Fetal Monitoring |

Birthing women are dealing with a hospital medical culture that has a very high rate of labor interventions (like induction and augmentation) that necessitate extremely close monitoring of fetal and maternal well-being. Procedures like fetal monitoring, IV fluids, and vaginal exams are easier when the mother is reclining. In addition, labor interventions that strengthen contractions raise the need for epidurals, which then often results in the mother laboring in a reclining position.

All of these things combine to create a powerful hospital culture that encourages a reclining, passive position for labor and birth. The mother is the passive patient that is having interventions done to her, the care providers are the active ones who are directing the labor. Even the language reinforces this; the doctor "delivers" the baby, rather than the woman "gives birth" to her child. As one researcher states:

Lithotomy position is not based on evidence and it comes with multitude of poor factors. This position is illogical, making the birth needlessly complicated, expensive, turning natural process into medical event and the laboring women to become simply the body on the delivery table to be relieved of their contents.The best option against all of this is to opt for a more natural childbirth where the mother is an active participant in birth instead of a passive patient who is being delivered. Women who go into labor spontaneously and who progress along their own bodies' timeline instead of being pushed to labor faster find it easier to assume the positions that their bodies tell them are needed, and they don't have to deal with most of the interventions that tend to force women into reclining positions.

|

| Campaign for Normal Birth, Royal College of Midwives |

However, the reality is that an intervention-free childbirth is uncommon in the hospital, sometimes interventions are truly medically necessary, and many women choose interventions like epidurals or inductions. Although more intervention-free childbirth is a worthy goal, greater variety in birthing positions does not depend on it. Alternative birth positions can still be used in women with interventions.

|

| Fetal monitoring in an upright sitting position on a birth ball |

EFM, induction, augmentation, IV fluids, and epidurals do not have to be a barrier to alternative positioning. It just requires being a little more creative. (A doula can be very helpful in this process.)

Care Provider Comfort and Convenience

Sadly, care provider comfort and convenience is a huge factor influencing maternal positioning.

Some care providers tell women they can use any position that they like in labor ("You can even stand on your head if you want"), but that for actually pushing out the baby, they have to be on their back or semi-sitting with knees apart or pulled back. Much of this is for the comfort of the provider, so they can be sitting comfortably or stand just as the baby is born.

But while it is understandable that providers want to stay within their comfort level, why should a care provider's comfort level take priority over the well-being and comfort of mother and baby? The top priority should be the mother and the baby, not the provider's comfort.

However, of course providers absolutely need to keep themselves safe too. They may be afraid they will strain their back or knees in another position, which is understandable.

Providers need to find a way to honor the mother's positioning needs while still finding a way to attend those positions in a manner that does not ergonomically hurt themselves.

With a little creativity, the needs of both parties can be served.

Care Provider Training

Some care providers tell women they can use any position that they like in labor ("You can even stand on your head if you want"), but that for actually pushing out the baby, they have to be on their back or semi-sitting with knees apart or pulled back. Much of this is for the comfort of the provider, so they can be sitting comfortably or stand just as the baby is born.

However, of course providers absolutely need to keep themselves safe too. They may be afraid they will strain their back or knees in another position, which is understandable.

|

| Alternative positions do not have to mean back strain for the attendant |

With a little creativity, the needs of both parties can be served.

Care Provider Training

Another huge barrier to alternative positions is the lack of training for providers in attending any other position.

Remember the 2013 medical student story from the first part of this post? She went through her entire rotation and NEVER saw any position other than a semi-reclining birth ─ in 2013, in a major hospital training program! This speaks very strongly to how ingrained this is in hospital culture.

Virtually all of the illustrations of birth that doctors see in their training involve the woman in the reclined or semi-sitting position. Notice the diagram above has the woman flat on her back. This is common in medical illustrations in obstetric textbooks.

Sadly, most care providers (and especially doctors) rarely see any position other than semi-sitting or reclining in their training, and they are taught to be very hands-on in manipulating the head and shoulders during birth. This makes them unsure how to do manipulations or to handle issues like shoulder dystocia when the physical orientation is different. As a result, some are very inflexible about letting the mother try different positions for the actual pushing out of the baby; they are afraid they will make a mistake when it counts most.

It is completely understandable that providers don't want to make a mistake that might harm a baby, but really, it's not that hard to re-educate oneself towards a different spatial orientation. All it takes is a willingness to learn about how to handle a different orientation, and a hospital and medical school culture that is willing to encourage such learning.

Medical schools would probably find that more mobility and more patience in labor would mean that less manipulation during birth would be needed. But because they come from a historical tradition of drugged mothers and drugged babies, they have been taught to use lots of hands-on manipulation during birth, and to fear positions that they see as interfering with their ability to do this manipulation.

Medical schools have much to teach their students in the few years they have them, but there is no good reason except tradition that handling alternative birth positions is not a meaningful part of the curriculum.

Compared to some of the other complex skills that doctors learn, learning about different spatial orientations for birth manipulations (when needed) would be relatively easy. Change would really take place if medical schools would just include this as part of the regular curriculum (more than just a brief mention, but actual practice with it). But when the teachers have rarely seen a birth outside of the usual positions, how are they going to teach meaningfully about it? And thus birthing position becomes a never-changing tradition in many hospitals.

There are some articles for doctors in the literature on how to re-orient themselves to attend births in different positions (see the free Canadian Family Physician article shown above), yet the information in them seems to be widely ignored in teaching and in practice.

It is LONG past time for medical school curriculum and residency programs to address alternative birth positions in a more meaningful way.

Remember the 2013 medical student story from the first part of this post? She went through her entire rotation and NEVER saw any position other than a semi-reclining birth ─ in 2013, in a major hospital training program! This speaks very strongly to how ingrained this is in hospital culture.

Virtually all of the illustrations of birth that doctors see in their training involve the woman in the reclined or semi-sitting position. Notice the diagram above has the woman flat on her back. This is common in medical illustrations in obstetric textbooks.

|

| Baby being birthed in an all-fours position. Notice the opposite orientation in this position, which is confusing for some providers |

Medical schools would probably find that more mobility and more patience in labor would mean that less manipulation during birth would be needed. But because they come from a historical tradition of drugged mothers and drugged babies, they have been taught to use lots of hands-on manipulation during birth, and to fear positions that they see as interfering with their ability to do this manipulation.

|

| Illustrations from Canadian Family Physician article, 1988 |

Compared to some of the other complex skills that doctors learn, learning about different spatial orientations for birth manipulations (when needed) would be relatively easy. Change would really take place if medical schools would just include this as part of the regular curriculum (more than just a brief mention, but actual practice with it). But when the teachers have rarely seen a birth outside of the usual positions, how are they going to teach meaningfully about it? And thus birthing position becomes a never-changing tradition in many hospitals.

|

| Illustrations from Canadian Family Physician article, 1988 |

It is LONG past time for medical school curriculum and residency programs to address alternative birth positions in a more meaningful way.

Conclusion

The vast majority of women in U.S. hospitals give birth in reclining or semi-sitting positions. This is not because their care providers are mean or wish them harm, it is because these positions have become rigidly ingrained into medical training, hospital culture, and popular culture. But it doesn't have to stay that way.

Although reclining positions are still seen frequently in many European and Australian hospitals too, alternative positions are more encouraged and accepted in these areas. In fact, most recent research on "alternative" positions is being done in Europe or Australia.

|

| German hospital birthing room |

[To be fair, some of it IS in some U.S. hospitals. But often it's only available on request or in a special room, not just a routine part of every birthing room. And too often, it's only for labor, not for the actual birth.]

|

| A hospital midwife attending a woman using a birth stool |

|

| Hospital birth in an all-fours position, attended by a family doctor. Photography from Canadian Family Physician, 1988 |

Women are more likely to find support for using alternative positions if their care provider believes strongly in physiologic birth, is supportive of natural childbirth, and has low intervention rates in labor.

Even if you are planning on having an epidural or are being induced, having a provider comfortable with natural childbirth increases your chances of using alternative positions despite these interventions.

To find out how supportive your care provider truly is of alternative positions, ask them to estimate what percentage of the births they've attended have been in non-recumbent positions. (Not labored in, but actually pushed the baby out in. Remember, many attendants are fine with mobility in labor but require women to be sitting or reclining for the actual "delivery" of the baby. You are looking for the ones that have experience and comfort with alternative positions for the actual birth too.)

It is mostly tradition, training, and comfort levels that keep reclining positions as the standard of care in many hospitals. But with education and flexibility, caregivers in the hospital can become more open to other positions and accommodate them in a way that respects the mother's needs as well as their own needs.

|

| Dangling and Supported Squat position in a hospital birth clinic in Peru |

It's about time these "alternative" positions became more widespread in medical schools, hospitals, and birthing clinics all around the world.

References

Position Ideas and Pictures

- http://www.rcmnormalbirth.org.uk/birthing-positions-in-practice/visual-aids-for-birthing-positions/ - pictures from the Campaign for Normal Birth, Royal College of Midwives

- http://www.lamazeinternational.org/p/cm/ld/fid=87 - evidence paper with pictures/video from Lamaze International

- http://evidencebasedbirth.com/what-is-the-evidence-for-pushing-positions/ - good evidence-based summary about birth positions for the pushing phase

- http://themisadventuresofastudentmidwife.blogspot.com/2011/06/birth.html - thoughtful and excellent essay from a student midwife on "Birth: A Technology of Gender" about internalized gender roles and how it influences modern childbirth (including birth positions)

- http://www.birthspirit.co.nz/the-obstetric-bed-resistance-in-action/ - good discussion of birth position and how it influences pelvic dimensions, with many references to medical literature

Pract Midwife. 2014 Apr;17(4):24-6. Mobility and upright positioning in labour. Westbury B. PMID: 24804420

SUMMARY: A study by the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) (2010) concluded that 49 per cent of women gave birth in the supine position. The RCM advocates getting women 'off the bed' in its campaign for normal birth. There has been much speculation as to why women labour on the bed, with some suggesting it is because women feel it is expected of them. Mobility and upright positioning in labour have countless benefits, with or without epidural anaesthesia, for both woman and fetus. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) supports the adoption of positions that women find most comfortable. Both midwives and students should fully explain the benefits of mobility and upright positioning in labour to women, preferably antenatally, to enable them to make informed decisions as to the positions they wish to adopt when in labour.Women Birth. 2012 Sep;25(3):100-6. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2011.05.001. Epub 2011 Jun 12.

What are the facilitators, inhibitors, and implications of birth positioning? A review of the literature. Priddis H1, Dahlen H, Schmied V. PMID: 21664208

BACKGROUND: From the historical literature it is apparent that birthing in an upright position was once common practice while today it appears that the majority of women within Western cultures give birth in a semi-recumbent position...RESULTS: The literature reports both the physical and psychological benefits for women when they are able to adopt physiological positions in labour, and birth in an upright position of their choice. Women who utilise upright positions during labour have a shorter duration of the first and second stage of labour, experience less intervention, and report less severe pain and increased satisfaction with their childbirth experience than women in a semi recumbent or supine/lithotomy position. Increased blood loss during third stage is the only disadvantage identified but this may be due to increased perineal oedema associated with upright positions. There is a lack of research into factors and/or practices within the current health system that facilitate or inhibit women to adopt various positions during labour andbirth. Upright birth positioning appears to occur more often within certain models of care, and birth settings, compared to others. The preferences for positions, and the philosophies of health professionals, are also reported to impact upon the position that women adopt during birth. CONCLUSION: Understanding the facilitators and inhibitors of physiological birth positioning, the impact of birth settings and how midwives and women perceive physiological birth positions, and how beliefs are translated into practice needs to be researched.