We have been talking about abnormal placentation in pregnancies after a cesarean, including:

- placental abruption (the placenta shearing off before the baby is ready to be born)

- placenta previa (a low-lying placenta that covers or nearly covers the cervix)

- placenta accreta (an abnormally attached placenta that has difficulty detaching after birth)

In Part One of this series, we summarized how the placenta works, what placenta accreta is, and its different levels of severity.

In Part Two of the series, we discussed the risk factors, symptoms, and incidence of placenta accreta, including its strong association with prior cesareans.

In Part Three of the series, we discussed the very serious risks associated with placenta accreta, both to the mother, to the baby, and to future pregnancies (if any).

Today, in Part Four, we will discuss the detection and diagnosis of accretas, the treatment options for accreta, things to be aware of if you are diagnosed with accreta, and share the personal story of someone with accreta.

*Warning: This post contains some graphic photos of accreta surgeries.

Placenta Accreta

In case there are any readers new to the series, let's briefly review the basics of how an abnormally attached placenta (accreta) happens.

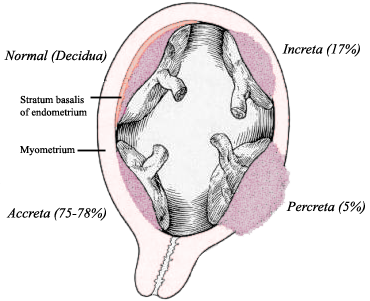

In a normal pregnancy, the decidua (lining of the uterus) prevents the placenta from invading the uterine wall. In placenta accreta, the decidua is thin or deficient due to damage or scar tissue from prior cesareans or other uterine instrumentation. This allows the placenta to attach itself directly into the maternal tissues. How deeply the placenta attaches determines the severity of the accreta.

In Placenta Accreta, the placenta forms an abnormal attachment to the wall of the uterus. About 75% of accretas are in this form.

In Placenta Increta, the placenta actually grows deeply into the muscle of the uterus (myometrium).

In Placenta Percreta, the placenta grows through the muscle of the uterus, through the outer layer, and often into adjacent structures nearby, like the bladder or bowels.

Fortunately, foreknowledge of an accreta, careful management protocols, and being in the right delivery setting can significantly lower the risk for mortality and morbidity.

Detection and Diagnosis of Accreta

As mentioned in Part Two of this series, bleeding after the first trimester is the most common symptom of placenta accreta.

If you experience bleeding after the first trimester or significant abdominal pain, this should be promptly investigated with a targeted ultrasound.

But what if you've had cesareans (or have other risk factors) and are now in a new pregnancy? Should you have an automatic ultrasound for placental placement, whether or not you have symptoms?

To Screen or Not to Screen?

Screening a woman with symptoms is a no-brainer. The benefits of confirming or ruling out an accreta far outweigh any potential risk for someone already presenting with possible symptoms.

A harder decision is whether to automatically screen all non-symptomatic women simply because they have risk factors like a prior cesarean, a history of infertility treatment, fibroid removals, or a D&C.

Remember, all prenatal testing ─ including ultrasound ─ has pros and cons. Although it can discover many complications ahead of time that may result in life-saving treatment, there is also a high rate of false-positives that can lead to panic and overtreatment. Furthermore, research has not shown that routine ultrasound screening in pregnancy improves outcomes.

On the other hand, selected screening in special situations can improve outcomes. The question is whether women who are not symptomatic but who simply have risk factors for accreta fall into this category.

Bottom line, there are no clear answers. This is a judgment call.

Accreta is a rare condition, even in women with risk factors, so chances are that most women without symptoms would be okay without doing a routine screening since accretas usually present with symptoms before term.

On the other hand, there are cases where women are asymptomatic before delivery but do have an accreta and experience significant difficulties during the birth. And research shows that outcomes do tend to improve if the condition is known about ahead of time so special plans can be made.

Because placenta accreta is such a serious complication, many care providers feel it is prudent to at have an ultrasound for placental placement at some point if you have risk factors for accreta (like a prior cesarean).

The more risk factors you have (i.e. multiple prior cesareans, several prior D&Cs, prior cesarean plus an IVF pregnancy etc.), the more important a screening ultrasound probably is.

Of course, you may decide that the cons of prenatal ultrasound are outweighed by its benefits in finding a possible accreta or other issues. It is always your option to decline any form of prenatal testing, but in making your decision, you do need to weigh the increased risk for abnormal placentation after a prior cesarean and the fact that detection of this condition before birth may help improve outcomes.

The consensus among most providers seems to be that the more cesareans or other uterine procedures you have had, the more consideration should be given to an ultrasound for placental placement ─ but again, the choice is always yours.

Timing

If you do decide on testing, don't do a placental placement ultrasound too early, since placentas often "move up" during pregnancy as the uterus expands.

What looks like a potential problem early in pregnancy often resolves itself fully by later pregnancy, so there's no need to raise anxiety levels by doing one in the first trimester.

Most providers feel that a screening ultrasound in the second or early third trimester is early enough if there are no other symptoms suggestive of a previa or accreta. On the other hand, if significant bleeding occurs or there is significant abdominal pain, that can be an early sign of severe placental issues, and an earlier ultrasound then becomes more sensible.

If you choose to do the standard ultrasound for birth defects at 18-20 weeks, they can check for placental placement then. Otherwise, if there are no symptoms, many providers are fine with waiting until the late second trimester or early third trimester to check for placental placement.

If in doubt, discuss the pros and cons of your unique situation with your provider and then make your decision.

What They Look For

If you do develop placenta accreta, it's important to know as much about it ahead of time as possible.

A targeted ultrasound usually shows what's needed. This is simply a regular ultrasound that lasts a little longer than usual and is specifically looking closely for certain issues (in this case, placentation). In some cases, a follow-up transvaginal ultrasound may also help clarify the diagnosis or rule it out.

According to ACOG (the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists), the following signs may indicate a possible accreta:

Additional Technology

Although regular "grayscale" ultrasounds are usually sufficient for diagnosis of most accretas, color Doppler, 3D ultrasound, or an MRI can sometimes be helpful to identify the degree of placental invasion.

MRIs may be particularly helpful if there is a posterior placenta (on the back of the uterus), if the ultrasound findings are ambiguous, or if a percreta with bladder involvement is suspected. Some resources also recommend an MRI for placental placement in women with "morbid obesity" and accreta risk factors if there is any difficulty getting a clear image with ultrasound alone.

Color Doppler, 3D ultrasound, and MRIs are not considered standard of care at this point and are not routinely done, even when an accreta is suspected. However, they can be useful adjunct tools to clarify the degree of accreta or to assist when ultrasound findings are inconclusive. Don't be hesitant to ask about this possibility if you feel the results are ambiguous at all.

Sometimes the diagnosis of accreta is less than definitive, especially with milder accretas. Since absolute confirmation of a diagnosis is always done in hindsight and needs lab analysis of both the placenta and the uterus (which would only happen after a hysterectomy), accreta diagnosis is most often based on physicians' opinion of test findings and their clinical impression of the situation.

This means that while obvious cases are usually caught, milder cases may not always be apparent until problems crop up during birth. It also means that sometimes a false positive diagnosis (thinking there's an accreta when there's really not) can occur.

So if in doubt, further testing with additional technology may help clarify ambiguous results.

Treatment of Accreta

In Part Three of this series, we discussed the risks of placenta accreta. Bottom line, the biggest risk with accretas is severe bleeding because the placenta cannot detach properly at birth.

In the short term, this can require multiple blood transfusions, cause a life-threatening blood clotting crisis, or necessitate a hysterectomy.

In the long term, it can cause postpartum anemia, difficulty breastfeeding, or even Sheehan's Syndrome (damage to the mother's pituitary gland, resulting in long-term health problems).

Since major blood loss is the biggest risk of an accreta and it is difficult to predict who is most at risk of severe blood loss, treatment of accretas usually revolves around trying to proactively prevent as much blood loss as possible.

To Remove the Placenta or Not to Remove the Placenta?

Trying to forcibly remove a stuck placenta is the strongest predictor for severe bleeding and other complications. Therefore, much of the treatment of placenta accreta involves avoiding removing the placenta at all.

Sometimes, in cases with very minor accretas, the placenta can be separated from the uterus with a little time and patience or the help of Dilation and Curettage (D&C). However, most of the time, a manual removal or a D&C is the last thing you want to try with accreta because it is often the beginning of major complications.

Because any attempt to deliver the placenta in a significant accreta can cause torrential bleeding, optimal treatment in these cases usually means leaving the placenta in place ("in situ") instead of trying to cut it out. The question is what to do with the placenta then.

Most OBs consider the standard of care for accreta to be a cesarean hysterectomy. After the baby is delivered, they leave the placenta intact in the uterus and then just take out the uterus with the placenta still attached, as can be seen here. This approach is widely regarded as having the best outcomes in research studies.

For women who desperately want another pregnancy and who are not bleeding too severely, other approaches are possible, although research is still being gathered on their feasibility and safety.

In the Expectant Management approach, doctors can deliver the baby, leave the placenta in place, suture the mother back up, and then wait for the body to break down and re-absorb the placenta. Alternatively, a late hysterectomy can be performed in a few weeks after the placenta has begun to break down and the risk of bleeding has diminished somewhat.

In the Medical Management approach, they do the same thing but also administer strong drugs like methotrexate to help break down the placenta. However, methotrexate is considered a contraindication to breastfeeding, and its efficacy is disputed.

The Expectant or Medical Management processes take months (and must be carefully monitored with follow-up ultrasounds, serial HCG measurements, and other tests), but can be effective. With this approach, some women are able to preserve their uterus, and a few women have gone on to have other children afterwards.

However, these approaches have significant risks. Sometimes the woman develops an infection from the leftover tissue, or can't stop hemorrhaging internally. Often additional procedures are needed to address an infection, bleeding, or blood clots. In a number of cases, a late hysterectomy is still needed (as in the picture above). In rare cases, women have been known to die from leaving the placenta and uterus in place.

Another possibility is Conservative Surgical Management. In this approach, doctors surgically resect the uterus when relatively minor degrees of accreta are present. Resection involves cutting out the part of the uterus with the implanted placenta, then suturing the sides of the uterus back together. There are a few case reports of this technique being used successfully, and even of pregnancy afterwards.

Yet another option is Uterine Arterial Embolization (UAE) ─ trying to deliberately cause a blood clot by injecting small particles into the arteries around the uterus in order to minimize bleeding. Without as much of its blood supply, the placenta then theoretically reabsorbs into the body more quickly. In one very small study, about 2/3 of the women who had UAE had successful outcomes, although there was a higher rate of secondary complications and longer hospitalizations. Other studies have also found good rates of success, although accompanied by significant complications at times. Some case reports even note successful term pregnancies after UAE.

These alternative treatments remain controversial. Research into them is evolving but the current consensus opinion from ACOG is that a cesarean hysterectomy is the best course of action:

However, if a mother strongly desires to preserve her fertility and is not experiencing severe bleeding, uterine-conserving approaches can be considered as long as the mother fully understands and accepts the possible risks. She should also understand that even if another pregnancy occurs, there is a substantial risk of another accreta as well.

If You Develop Placenta Accreta

Being told you might have placenta accreta is scary. Decisions can seem overwhelming and information for making them may be sparse.

This section is to help you understand the probable choices around your birth and why many procedures are used. Of course, each woman's situation is different and differences in circumstances may mean that your optimal treatment can be different from someone else's optimal treatment.

You should know that because accreta has been so rare in the past, there are no randomized trials to determine the most effective course of treatment. This means that no one is completely sure of the best way to handle an accreta. Therefore, it's vital that you understand your choices and discuss the pros and cons of each carefully with your provider.

No medical advice should be inferred from this information; it is provided simply to suggest things to discuss with your providers as you consider your choices. You should do your own research and consult your providers closely as you contemplate your options.

First, Don't Panic

Being diagnosed with placenta accreta can be very frightening. Research summaries often emphasize worst-possible outcomes. Support groups, while valuable, can have scary stories of complications and problems. Even this post has to emphasize the risks so that women fully understand the possibilities, but that doesn't mean they will happen to you.

Remember, while it's important to be aware of the significant risks of accreta, it's also important to keep the risks in perspective.

Most women with accretas have reasonably good outcomes. And knowing about the accreta ahead of time has been shown to significantly improve outcomes and minimize morbidity in many cases.

So while there is reason to be concerned and women should spend time educating themselves about this condition, it's also important to keep the risks in perspective and know that chances are strong that you and your baby will be okay. If you start to get overwhelmed, take a deep breath and keep reminding yourself of this fact.

Reach out to other moms who have been through accreta or other complicated pregnancies and get some support from people who really "get" what you are going through. In them, you may find your biggest source of sanity and courage.

Where to Deliver and Who Should Be There

Accretas make for complicated surgeries, but they are fairly rare surgeries. Because they don't happen very often, you want an expert who is experienced in dealing with them. Therefore, your local care provider should refer you to a team of maternal-fetal medicine specialists at a large hospital in your area. Research shows improved outcomes when accretas are delivered by multidisciplinary specialist teams instead of standard obstetric care.

Delivery should not take place in your local community hospital, but rather in a regional or specialist ("tertiary") hospital with access to significant blood reserves and an established protocol for severe hemorrhage. This offers you the best chance at a good outcome.

ACOG recommends consulting with specialists ahead of time and having as many on call during the surgery as possible:

Hopefully, you will not need any of these specialists, but the idea is to have a strong plan ahead of time and to have consultants on call in case complications occur. Most will never be called upon, but it's best to have them ready just in case.

When and How to Deliver

There are many aspects unique to delivering an accreta pregnancy. Here are a few to discuss with your care provider.

Planned Cesareans

If a significant accreta is present, you will likely need to deliver via a planned cesarean section.

Very minor or questionable accretas can sometimes have a vaginal delivery, then wait and see if spontaneous placental separation occurs, but even minor accretas can still result in significant hemorrhage and complications that necessitate a cesarean or hysterectomy, so most providers prefer a planned cesarean.

Since emergency cesareans have poorer outcomes with accretas, there is a strong case to be made that a planned cesarean is the best choice in order to have the necessary specialists standing by and plenty of blood products on hand if needed. Of course, much will depend on the degree of accreta that is expected, but most experts feel that known accretas are best delivered by cesarean.

Prematurity

Most accreta pregnancies deliver before full-term, adding the complications of prematurity to the many other issues associated with accreta. This means more challenges with learning to nurse, difficulties in sustaining body temperature and blood sugar, and possible issues with brain bleeds, vision issues, infections, and other problems.

Many preemies do amazingly well these days, but dealing with a preemie can be an emotional rollercoaster. The family involved needs to start educating itself about prematurity issues and lining up support in case the baby does arrive early. A few resources on prematurity are listed below in the Resources Section, but a quick internet search will bring up many more.

Prenatal Hospitalization

If you have been experiencing intermittent significant bleeding episodes or have bled before 32 weeks, your care providers will quite likely want you hospitalized for some time before the scheduled delivery, since these cases are more at risk for emergency delivery and this is best handled with immediately available resources.

Even if you are not having major prenatal bleeds, you and your provider need to be ready for an emergency delivery in case one suddenly becomes necessary. Therefore, if you do not live near the tertiary hospital where you will deliver, your specialists may recommend that you be hospitalized before the birth or that you take a temporary apartment very close by. At the very least, you should have a plan for childcare for any older children and a packed bag ready to go should you suddenly need to be hospitalized.

Being put on bedrest or confined to the hospital for weeks ahead of the birth can be very stressful. Emotional support from groups like Sidelines National Support Group can be invaluable if you experience this.

Timing of Delivery

If there is no need for an early emergency delivery, most resources recommend delivery between 34 and 36 weeks when accreta is present. This timing seems to offer the best balance between awaiting fetal maturity yet avoiding significant hemorrhage, since one study found that more than 90% of their patients with accreta experienced a significant bleed after about 35 weeks. Some doctors will agree to wait a bit longer, depending on the circumstances, but most agree the baby should be delivered before term.

One important question is fetal lung maturity before delivery. If a very early delivery looks likely, then a prenatal course of steroids may be administered in hopes that this will help the baby's lungs to mature before delivery must occur. The OB then needs to decide whether or not to do an amniocentesis before delivery to confirm fetal lung maturity.

If the pregnancy makes it to the usual delivery time of 34-36 weeks, an amnio is more questionable. Current opinion is that doing an amnio does not seem to improve outcome, but many doctors prefer to err on the side of caution and do one anyway.

ACOG's accreta guidelines suggest individualizing the timing of delivery, depending on each person's circumstances:

The type of incision used is left up to the individual doctor, based on the circumstances of the case.

Most resources strongly recommend against cutting into the placenta at all. This will help minimize bleeding.

If the placenta is low-lying (placenta previa with accreta) or covers most of the anterior wall, doctors may decide to use a vertical (up-down) instead of the usual low horizontal side-to-side incision.

Sometimes the uterus is taken out entirely to facilitate an incision away from an anterior accreta.

In the photo to the left, the uterus has been taken out so the doctors can do a fundal (top of uterus) and posterior (on the back side of the uterus) incision in order to keep the placenta and its bladder invasion intact before the hysterectomy.

During the surgery, some doctors have the mother's legs placed in special stirrups. This might seem strange for a cesarean delivery, but it is a precaution so that both vaginal and abdominal packing can be placed if bleeding is significant.

Antibiotics will be administered just before or right as the surgery is started. Because of the increased risk for infection, accreta patients may also receive additional doses after the surgery, if surgery is prolonged, or if uterus-conserving techniques are chosen. If you are a woman of size, don't forget to discuss the possibility of weight-based antibiotic dosing or extended dosing with your doctor in order to minimize your risk for infection. Post-operatively, probiotics may help promote gut health if you experience gastrointestinal problems from the antibiotics.

Preparing for Blood Loss

Because maternal blood loss is one of the biggest risks associated with accretas, ACOG recommends having strong maternal hemoglobin levels in advance of the surgery.

This can be done with iron pills, with herbal preparations (like Floradix, alfalfa, dandelion roots, nettle leaves, beet roots, etc.), or with food (like red meat, dark meat chicken, eggs, cashews, lentils, molasses, dried fruit, seaweed, leafy greens, pumpkin seeds, etc.). Take iron-rich foods with vitamin C, as this increases absorption strongly. Supplementation with Vitamin B-6 may also be helpful. On the other hand, don't take iron pills or foods with dairy products, caffeine, or antacids, as these inhibit absorption.

Your blood should be typed and matched before surgery, and blood products should be readily available in the O.R. during surgery. The blood blank should also be on call to provide additional units quickly if needed. In some areas, they may also be asked to stock certain additives that may also help if a severe hemorrhage occurs.

ACOG also recommends considering having a way to salvage the mother's own blood loss and return it to her during the surgery.

You are quite likely to need a blood transfusion at some point in your recovery if you have a significant accreta. Many women require multiple transfusions. Be prepared for this issue, and for the strong likelihood of hysterectomy if bleeding is not able to be controlled.

Anesthesia

The best anesthesia choice for accreta patients is still debated.

Many OBs strongly prefer general anesthesia. This offers the advantage of an unlimited amount of surgery time (in case the surgery is complicated). It also keeps the patient unconscious during what may be a difficult and scary surgery (most percretas are done with general anesthesia, for example). The biggest disadvantage of a general is that it tends to affect the baby negatively, and doesn't provide very good post-op pain relief.

Some OBs are fine with regional anesthesia (spinal, epidural, or combined spinal-epidural [CSE]). This allows the mother to be conscious for the baby's birth, improves fetal Apgar scores, and tends to offer better post-partum pain control as well. However, most regional anesthesia (except CSE) will not last long enough if surgery becomes prolonged. In addition, most surgeons don't want the patient awake if the surgery gets complicated or if massive hemorrhage occurs.

Some OBs will allow a combination of anesthesia choices when circumstances allow. The mother may start with a spinal or epidural so she can be awake for the baby's birth and so that the baby has minimal exposure to the strong drugs of general anesthesia. Once the baby is delivered and the surgeons have evaluated placental attachment, they may stay with regional anesthesia or opt to convert to general anesthesia so it will work for as long as needed and so that the patient is not awake in case major complications occur.

An anesthesia consult ahead of delivery is very important. You and your care providers should discuss the pros and cons of various approaches, your preferences, and the unique circumstances of your condition that may affect anesthesia choice.

Pre-Operative Precautions

Before a planned cesarean, there are several routine precautions often employed to help improve outcome.

Many providers recommend a special skin preparation routine the day before or the day of the cesarean. This may help reduce the risk for infection, although evidence is not yet clear on the best protocol for skin preparation.

Intravenous access (I.V.) is always placed before any surgery, but your doctors will probably recommend that you have large-bore IV lines or an arterial IV line placed before surgery. This allows a large volume of fluids or blood products to be delivered more quickly in case of hemorrhage.

Many hospitals now use pneumatic compression stockings for all surgical patients. These inflate and deflate on the legs to lower the risk for the development of blood clots that could travel to the lungs. If the standard size does not fit, there are usually pneumatic compression devices that can be used instead of compression stockings. These should be placed before the operation and stay in use until the patient is walking regularly afterwards.

In addition to these procedures, some doctors choose to place a stent (small tube) or catheters in the ureters before a cesarean hysterectomy, which may lessen the risk for damage to the ureters. Again, research is ongoing into this procedure.

Additional Blood Loss Treatment Options

Doctors may choose to use additional precautions against severe bleeding and abdominal organ damage, but these options are more controversial. Research is ongoing into their benefits and risks.

Some OBs place an internal balloon catheter pre-operatively in the arteries around the uterus so that if severe bleeding does occur, they can inflate the balloon to try and shut down the bleeding. A recent literature review of this procedure found conflicting results and recommended further research.

Doctors can also clamp off the uterine arteries in order to reduce the amount of bleeding during the cesarean. This may not be effective because there are many alternative sources of blood supply to this area, but it is another tool in the arsenal that doctors can consider.

Another option is the afore-mentioned Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE). While UAE is usually done in non-pregnant women to treat fibroids, it can also help lessen bleeding with an accreta, either during a hysterectomy or post-operatively. And, as previously mentioned, it may also be tried in a uterus-conserving management of accreta.

It should be noted that all of these additional procedures are still controversial. ACOG notes:

Birth Plan

Accreta can have such variable outcomes that it is important to have a plan in place for various potential outcomes. This can help guide your doctors about your wishes if you are not available to consult right away.

Things you might want to consider putting into your plan include guidelines for infant feeding, kangaroo care for your partner, preferences regarding newborn procedures and vaccinations, etc. You might also want to consider requesting milk from a human milk donor bank until you are able to produce your own (which might be delayed due to blood loss or placental fragments left inside).

After the Delivery

You will probably be in the hospital for a longer recovery time than most cesarean mothers. You may experience significant abdominal pain afterwards (more than the normal cesarean pain) because of internal bleeding and the surgical trauma of a difficult operation. Wound healing may be somewhat delayed as your body tries to cope with the demands of such a significant challenge to the system.

One Australian study found that about half of women with accreta developed some sort of surgical complication (usually bladder injury), and about 20% needed to have additional surgical procedures later on. If you develop blood in your urine, this should be evaluated right away. In addition, hidden bleeding and infection may develop afterwards, so be sure to get prompt attention if you start to feel more unwell than usual.

It is very important to support your body nutritionally to help it recover from significant blood loss. Plan on getting plenty of B vitamins and iron after the birth in order to help rebuild your blood supply. Drink plenty of water. Nuts, leafy greens, dried fruit, and red meat are good natural sources of iron, folate, other B vitamins, and the A vitamins so vital to healing.

Long-term, you should be tested several times for postpartum anemia. The majority of women with accreta suffer a quite significant blood loss and this can cause long-lasting anemia. Although many care providers are aware of this, it sometimes gets overlooked as a "minor" concern once the life-threatening crisis is over, and follow-up testing can be neglected. Yet it is a critical quality-of-life issue for your healing and long-term recovery, so don't be hesitant to be assertive about having your levels checked.

Remember that hemorrhage, retained placenta, and anemia can also all negatively negatively impact milk supply, and prematurity can make it difficult for babies to latch on efficiently. Although some women in this situation are able to make breastfeeding work without problems, don't hesitate to consult an IBCLC (Internationally Board-Certified Lactation Consultant) for help if needed.

In time, adequate milk supply may develop with regular pumping, but in the meantime, you may need to supplement with donated human milk or formula while proactively promoting milk supply (see http://www.lowmilksupply.org/). Information about supplementation can be found here. And a great resource for unbiased, non-judgmental support for mothers struggling with breastfeeding difficulties can be found here.

If you experienced a very severe hemorrhage during delivery, be aware that this can sometimes damage your pituitary gland (Sheehan's Syndrome). Thyroid issues, fatigue, body hair loss, and adrenal issues are common long-term complications. If you cannot breastfeed and the return of your period is delayed or quite irregular, ask to be for tested for Sheehan's Syndrome. Also be aware that this complication sometimes doesn't show up until years later, so you may need to be retested several times over the years.

Be sure to plan for a longer recovery time and extra help after the delivery, since recovery is likely to be harder after an accreta. Don't rush your recovery, but take plenty of time to rest and let your body heal slowly. Sleep, good nutrition, and taking your recovery slowly are your best allies in this.

Having a baby is hard enough on the body; dealing with an accreta and blood loss on top of that is even harder. Get extra help around the house (a postpartum doula may be helpful) and be sure to accept the help of friends, extended family, and neighbors as much as circumstances allow. Your job is simply to heal and to take care of the baby. Let your partner and others step up to take care of everything else.

Summary

Placenta Accreta is a rare but very serious complication that is associated with prior uterine instrumentation procedures. Although it can occur after a number of different procedures, it is most strongly associated with prior cesarean. It is most common with rising numbers of prior cesareans, but can occur even in women with only one prior cesarean.

Accretas come in three different levels of severity, but make no mistake, all are potentially life-threatening. Although minor degrees of accreta can often be resolved without major repercussions, the potential for serious complications is always there and must be taken seriously. And the potential complications with the most severe forms are sobering indeed.

Of course, it's only fair to point out that even though the risk for abnormal placentation rises with each cesarean, most women with prior cesareans do not experience placenta previa or accreta. And most cesareans go well, even higher-order cesareans. So if you have had cesareans before, don't panic. Chances are you'll be okay.

However, from a public health point of view, the take-home message is that risks start rising rapidly as the total number of cesareans increase.

Complications like previa and accreta are more common after three to four or more cesareans. However, sometimes these complications happen when a woman has "only" had one or two prior cesareans. Just because you've only had one or two cesareans instead of four doesn't mean you aren't at risk. It all depends on how well your uterus was able to repair itself and exactly where an embryo implants.

And although the absolute risk for previa and accreta overall is low, it's far higher than it is in women who have never had any cesareans.

Don't forget, sometimes there are babies and women who die from placenta accreta/percreta, or have very near misses.

At the very least, it often results in severe hemorrhage, hysterectomy, loss of fertility, uterine rupture, and significant damage to the urological system or abdomen of the mother, not to mention prematurity in the baby.

This is why it is important to avoid the first cesarean whenever possible, to not automatically schedule repeat cesareans in most women, and to make sure that VBAC stays an option for as many women as possible.

Unfortunately, this is the exact opposite of what's happening in many places right now. And that's why the world will continue to see a strong rise in the number of women experiencing placenta accreta and all its complications. As one recent study concluded:

A Concluding StoryIn case there are any readers new to the series, let's briefly review the basics of how an abnormally attached placenta (accreta) happens.

In a normal pregnancy, the decidua (lining of the uterus) prevents the placenta from invading the uterine wall. In placenta accreta, the decidua is thin or deficient due to damage or scar tissue from prior cesareans or other uterine instrumentation. This allows the placenta to attach itself directly into the maternal tissues. How deeply the placenta attaches determines the severity of the accreta.

|

| image from fetalsono.com |

In Placenta Accreta, the placenta forms an abnormal attachment to the wall of the uterus. About 75% of accretas are in this form.

In Placenta Percreta, the placenta grows through the muscle of the uterus, through the outer layer, and often into adjacent structures nearby, like the bladder or bowels.

Fortunately, foreknowledge of an accreta, careful management protocols, and being in the right delivery setting can significantly lower the risk for mortality and morbidity.

Detection and Diagnosis of Accreta

As mentioned in Part Two of this series, bleeding after the first trimester is the most common symptom of placenta accreta.

If you experience bleeding after the first trimester or significant abdominal pain, this should be promptly investigated with a targeted ultrasound.

But what if you've had cesareans (or have other risk factors) and are now in a new pregnancy? Should you have an automatic ultrasound for placental placement, whether or not you have symptoms?

To Screen or Not to Screen?

Screening a woman with symptoms is a no-brainer. The benefits of confirming or ruling out an accreta far outweigh any potential risk for someone already presenting with possible symptoms.

A harder decision is whether to automatically screen all non-symptomatic women simply because they have risk factors like a prior cesarean, a history of infertility treatment, fibroid removals, or a D&C.

Remember, all prenatal testing ─ including ultrasound ─ has pros and cons. Although it can discover many complications ahead of time that may result in life-saving treatment, there is also a high rate of false-positives that can lead to panic and overtreatment. Furthermore, research has not shown that routine ultrasound screening in pregnancy improves outcomes.

On the other hand, selected screening in special situations can improve outcomes. The question is whether women who are not symptomatic but who simply have risk factors for accreta fall into this category.

Bottom line, there are no clear answers. This is a judgment call.

Accreta is a rare condition, even in women with risk factors, so chances are that most women without symptoms would be okay without doing a routine screening since accretas usually present with symptoms before term.

On the other hand, there are cases where women are asymptomatic before delivery but do have an accreta and experience significant difficulties during the birth. And research shows that outcomes do tend to improve if the condition is known about ahead of time so special plans can be made.

Because placenta accreta is such a serious complication, many care providers feel it is prudent to at have an ultrasound for placental placement at some point if you have risk factors for accreta (like a prior cesarean).

The more risk factors you have (i.e. multiple prior cesareans, several prior D&Cs, prior cesarean plus an IVF pregnancy etc.), the more important a screening ultrasound probably is.

Of course, you may decide that the cons of prenatal ultrasound are outweighed by its benefits in finding a possible accreta or other issues. It is always your option to decline any form of prenatal testing, but in making your decision, you do need to weigh the increased risk for abnormal placentation after a prior cesarean and the fact that detection of this condition before birth may help improve outcomes.

The consensus among most providers seems to be that the more cesareans or other uterine procedures you have had, the more consideration should be given to an ultrasound for placental placement ─ but again, the choice is always yours.

Timing

If you do decide on testing, don't do a placental placement ultrasound too early, since placentas often "move up" during pregnancy as the uterus expands.

What looks like a potential problem early in pregnancy often resolves itself fully by later pregnancy, so there's no need to raise anxiety levels by doing one in the first trimester.

Most providers feel that a screening ultrasound in the second or early third trimester is early enough if there are no other symptoms suggestive of a previa or accreta. On the other hand, if significant bleeding occurs or there is significant abdominal pain, that can be an early sign of severe placental issues, and an earlier ultrasound then becomes more sensible.

If you choose to do the standard ultrasound for birth defects at 18-20 weeks, they can check for placental placement then. Otherwise, if there are no symptoms, many providers are fine with waiting until the late second trimester or early third trimester to check for placental placement.

If in doubt, discuss the pros and cons of your unique situation with your provider and then make your decision.

What They Look For

If you do develop placenta accreta, it's important to know as much about it ahead of time as possible.

A targeted ultrasound usually shows what's needed. This is simply a regular ultrasound that lasts a little longer than usual and is specifically looking closely for certain issues (in this case, placentation). In some cases, a follow-up transvaginal ultrasound may also help clarify the diagnosis or rule it out.

According to ACOG (the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists), the following signs may indicate a possible accreta:

The ultrasonographic features suggestive of placenta accreta include irregularly shaped placental lacunae (vascular spaces) within the placenta, thinning of the myometrium overlying the placenta, loss of the retroplacental “clear space,” protrusion of the placenta into the bladder, increased vascularity of the uterine serosa–bladder interface, and turbulent blood flow through the lacunae on Doppler ultrasonography. The presence and increasing number of lacunae within the placenta at 15–20 weeks of gestation have been shown to be the most predictive ultrasonographic signs of placenta accreta, with a sensitivity of 79% and a positive predictive value of 92%. These lacunae may result in the placenta having a “moth-eaten” or “Swiss cheese” appearance.If in doubt, don't be afraid to request a second opinion or another scan. If accreta is suspected, ask for a consult with a specialist associated with a center that does a lot of prenatal testing. These are the people with the most sophisticated equipment and greatest expertise in trying to detect whether or not there is a problem.

Additional Technology

|

| MRI image of possible percreta in patient with 2 prior D&Cs "P" marks placenta previa (low-lying, below head) arrows point to possible bladder involvement Image from Ochsner 2011 |

MRIs may be particularly helpful if there is a posterior placenta (on the back of the uterus), if the ultrasound findings are ambiguous, or if a percreta with bladder involvement is suspected. Some resources also recommend an MRI for placental placement in women with "morbid obesity" and accreta risk factors if there is any difficulty getting a clear image with ultrasound alone.

Color Doppler, 3D ultrasound, and MRIs are not considered standard of care at this point and are not routinely done, even when an accreta is suspected. However, they can be useful adjunct tools to clarify the degree of accreta or to assist when ultrasound findings are inconclusive. Don't be hesitant to ask about this possibility if you feel the results are ambiguous at all.

Sometimes the diagnosis of accreta is less than definitive, especially with milder accretas. Since absolute confirmation of a diagnosis is always done in hindsight and needs lab analysis of both the placenta and the uterus (which would only happen after a hysterectomy), accreta diagnosis is most often based on physicians' opinion of test findings and their clinical impression of the situation.

This means that while obvious cases are usually caught, milder cases may not always be apparent until problems crop up during birth. It also means that sometimes a false positive diagnosis (thinking there's an accreta when there's really not) can occur.

So if in doubt, further testing with additional technology may help clarify ambiguous results.

Treatment of Accreta

,+image+NIH.jpg) |

| Placenta Percreta - notice how the placenta is growing into the uterus Image from Tikkanen 2011, J Med Case Rep |

In the short term, this can require multiple blood transfusions, cause a life-threatening blood clotting crisis, or necessitate a hysterectomy.

In the long term, it can cause postpartum anemia, difficulty breastfeeding, or even Sheehan's Syndrome (damage to the mother's pituitary gland, resulting in long-term health problems).

Since major blood loss is the biggest risk of an accreta and it is difficult to predict who is most at risk of severe blood loss, treatment of accretas usually revolves around trying to proactively prevent as much blood loss as possible.

To Remove the Placenta or Not to Remove the Placenta?

Trying to forcibly remove a stuck placenta is the strongest predictor for severe bleeding and other complications. Therefore, much of the treatment of placenta accreta involves avoiding removing the placenta at all.

Sometimes, in cases with very minor accretas, the placenta can be separated from the uterus with a little time and patience or the help of Dilation and Curettage (D&C). However, most of the time, a manual removal or a D&C is the last thing you want to try with accreta because it is often the beginning of major complications.

Because any attempt to deliver the placenta in a significant accreta can cause torrential bleeding, optimal treatment in these cases usually means leaving the placenta in place ("in situ") instead of trying to cut it out. The question is what to do with the placenta then.

Most OBs consider the standard of care for accreta to be a cesarean hysterectomy. After the baby is delivered, they leave the placenta intact in the uterus and then just take out the uterus with the placenta still attached, as can be seen here. This approach is widely regarded as having the best outcomes in research studies.

For women who desperately want another pregnancy and who are not bleeding too severely, other approaches are possible, although research is still being gathered on their feasibility and safety.

In the Expectant Management approach, doctors can deliver the baby, leave the placenta in place, suture the mother back up, and then wait for the body to break down and re-absorb the placenta. Alternatively, a late hysterectomy can be performed in a few weeks after the placenta has begun to break down and the risk of bleeding has diminished somewhat.

|

| placenta percreta left in situ methotrexate administered, hysterectomy 7 weeks later Image from Tikkanen 2011, J Med Case Rep |

The Expectant or Medical Management processes take months (and must be carefully monitored with follow-up ultrasounds, serial HCG measurements, and other tests), but can be effective. With this approach, some women are able to preserve their uterus, and a few women have gone on to have other children afterwards.

However, these approaches have significant risks. Sometimes the woman develops an infection from the leftover tissue, or can't stop hemorrhaging internally. Often additional procedures are needed to address an infection, bleeding, or blood clots. In a number of cases, a late hysterectomy is still needed (as in the picture above). In rare cases, women have been known to die from leaving the placenta and uterus in place.

Another possibility is Conservative Surgical Management. In this approach, doctors surgically resect the uterus when relatively minor degrees of accreta are present. Resection involves cutting out the part of the uterus with the implanted placenta, then suturing the sides of the uterus back together. There are a few case reports of this technique being used successfully, and even of pregnancy afterwards.

Yet another option is Uterine Arterial Embolization (UAE) ─ trying to deliberately cause a blood clot by injecting small particles into the arteries around the uterus in order to minimize bleeding. Without as much of its blood supply, the placenta then theoretically reabsorbs into the body more quickly. In one very small study, about 2/3 of the women who had UAE had successful outcomes, although there was a higher rate of secondary complications and longer hospitalizations. Other studies have also found good rates of success, although accompanied by significant complications at times. Some case reports even note successful term pregnancies after UAE.

These alternative treatments remain controversial. Research into them is evolving but the current consensus opinion from ACOG is that a cesarean hysterectomy is the best course of action:

[The alternative management] approach should be considered only when the patient has a strong desire for future fertility as well as hemodynamic stability, normal coagulation status, and is willing to accept the risks involved in this conservative approach. The patient should be counseled that the outcome of this approach is unpredictable and that there is an increased risk of significant complications as well as the need for later hysterectomy. Reported cases of subsequent successful pregnancy in patients treated with this approach are rare. This approach should be abandoned and hysterectomy performed if excessive bleeding is noted...Except in specific cases, hysterectomy remains the treatment of choice for patients with placenta accreta.So while uterus-conserving treatment is possible and there is a fair amount of excited research on the possibility, the trials have been relatively small so far and outcomes have been mixed. Experts at this point definitely favor a cesarean hysterectomy in most cases.

However, if a mother strongly desires to preserve her fertility and is not experiencing severe bleeding, uterine-conserving approaches can be considered as long as the mother fully understands and accepts the possible risks. She should also understand that even if another pregnancy occurs, there is a substantial risk of another accreta as well.

If You Develop Placenta Accreta

Being told you might have placenta accreta is scary. Decisions can seem overwhelming and information for making them may be sparse.

This section is to help you understand the probable choices around your birth and why many procedures are used. Of course, each woman's situation is different and differences in circumstances may mean that your optimal treatment can be different from someone else's optimal treatment.

You should know that because accreta has been so rare in the past, there are no randomized trials to determine the most effective course of treatment. This means that no one is completely sure of the best way to handle an accreta. Therefore, it's vital that you understand your choices and discuss the pros and cons of each carefully with your provider.

No medical advice should be inferred from this information; it is provided simply to suggest things to discuss with your providers as you consider your choices. You should do your own research and consult your providers closely as you contemplate your options.

First, Don't Panic

Being diagnosed with placenta accreta can be very frightening. Research summaries often emphasize worst-possible outcomes. Support groups, while valuable, can have scary stories of complications and problems. Even this post has to emphasize the risks so that women fully understand the possibilities, but that doesn't mean they will happen to you.

Remember, while it's important to be aware of the significant risks of accreta, it's also important to keep the risks in perspective.

Most women with accretas have reasonably good outcomes. And knowing about the accreta ahead of time has been shown to significantly improve outcomes and minimize morbidity in many cases.

So while there is reason to be concerned and women should spend time educating themselves about this condition, it's also important to keep the risks in perspective and know that chances are strong that you and your baby will be okay. If you start to get overwhelmed, take a deep breath and keep reminding yourself of this fact.

Reach out to other moms who have been through accreta or other complicated pregnancies and get some support from people who really "get" what you are going through. In them, you may find your biggest source of sanity and courage.

Where to Deliver and Who Should Be There

Accretas make for complicated surgeries, but they are fairly rare surgeries. Because they don't happen very often, you want an expert who is experienced in dealing with them. Therefore, your local care provider should refer you to a team of maternal-fetal medicine specialists at a large hospital in your area. Research shows improved outcomes when accretas are delivered by multidisciplinary specialist teams instead of standard obstetric care.

Delivery should not take place in your local community hospital, but rather in a regional or specialist ("tertiary") hospital with access to significant blood reserves and an established protocol for severe hemorrhage. This offers you the best chance at a good outcome.

ACOG recommends consulting with specialists ahead of time and having as many on call during the surgery as possible:

Delivery planning may involve an anesthesiologist, obstetrician, pelvic surgeon such as a gynecologic oncologist, intensivist, maternal–fetal medicine specialist, neonatologist, urologist, hematologist, and interventional radiologist to optimize the patient’s outcome. To enhance patient safety, it is important that the delivery be performed by an experienced obstetric team that includes an obstetric surgeon, with other surgical specialists, such as urologists, general surgeons, and gynecologic oncologists, available if necessary.These specialists are to cover any possible severe complications that lie beyond the normal scope of training for most OBs. For example, if difficulty with blood clotting develops, a hematologist may need to be called in. If the baby is very premature, a neonatologist may be needed. If there is a percreta that has invaded nearby organs, a urologist, general surgeon, or gynecologic oncologist may be needed. An interventional radiologist may be utilized if they decide to use UAE (see above).

Hopefully, you will not need any of these specialists, but the idea is to have a strong plan ahead of time and to have consultants on call in case complications occur. Most will never be called upon, but it's best to have them ready just in case.

When and How to Deliver

There are many aspects unique to delivering an accreta pregnancy. Here are a few to discuss with your care provider.

Planned Cesareans

|

| Image from singhealth.com.sg |

Very minor or questionable accretas can sometimes have a vaginal delivery, then wait and see if spontaneous placental separation occurs, but even minor accretas can still result in significant hemorrhage and complications that necessitate a cesarean or hysterectomy, so most providers prefer a planned cesarean.

Since emergency cesareans have poorer outcomes with accretas, there is a strong case to be made that a planned cesarean is the best choice in order to have the necessary specialists standing by and plenty of blood products on hand if needed. Of course, much will depend on the degree of accreta that is expected, but most experts feel that known accretas are best delivered by cesarean.

Prematurity

Most accreta pregnancies deliver before full-term, adding the complications of prematurity to the many other issues associated with accreta. This means more challenges with learning to nurse, difficulties in sustaining body temperature and blood sugar, and possible issues with brain bleeds, vision issues, infections, and other problems.

Many preemies do amazingly well these days, but dealing with a preemie can be an emotional rollercoaster. The family involved needs to start educating itself about prematurity issues and lining up support in case the baby does arrive early. A few resources on prematurity are listed below in the Resources Section, but a quick internet search will bring up many more.

Prenatal Hospitalization

If you have been experiencing intermittent significant bleeding episodes or have bled before 32 weeks, your care providers will quite likely want you hospitalized for some time before the scheduled delivery, since these cases are more at risk for emergency delivery and this is best handled with immediately available resources.

Even if you are not having major prenatal bleeds, you and your provider need to be ready for an emergency delivery in case one suddenly becomes necessary. Therefore, if you do not live near the tertiary hospital where you will deliver, your specialists may recommend that you be hospitalized before the birth or that you take a temporary apartment very close by. At the very least, you should have a plan for childcare for any older children and a packed bag ready to go should you suddenly need to be hospitalized.

Being put on bedrest or confined to the hospital for weeks ahead of the birth can be very stressful. Emotional support from groups like Sidelines National Support Group can be invaluable if you experience this.

Timing of Delivery

If there is no need for an early emergency delivery, most resources recommend delivery between 34 and 36 weeks when accreta is present. This timing seems to offer the best balance between awaiting fetal maturity yet avoiding significant hemorrhage, since one study found that more than 90% of their patients with accreta experienced a significant bleed after about 35 weeks. Some doctors will agree to wait a bit longer, depending on the circumstances, but most agree the baby should be delivered before term.

One important question is fetal lung maturity before delivery. If a very early delivery looks likely, then a prenatal course of steroids may be administered in hopes that this will help the baby's lungs to mature before delivery must occur. The OB then needs to decide whether or not to do an amniocentesis before delivery to confirm fetal lung maturity.

If the pregnancy makes it to the usual delivery time of 34-36 weeks, an amnio is more questionable. Current opinion is that doing an amnio does not seem to improve outcome, but many doctors prefer to err on the side of caution and do one anyway.

ACOG's accreta guidelines suggest individualizing the timing of delivery, depending on each person's circumstances:

The timing of delivery in cases of suspected placenta accreta must be individualized. This decision should be made jointly with the patient, obstetrician, and neonatologist...A guiding principle in management is to achieve a planned delivery because data suggest greater blood loss and complications in emergent cesarean hysterectomy versus planned cesarean hysterectomy. Although a planned delivery is the goal, a contingency plan for emergency delivery should be developed for each patient, which may include following an institutional protocol for maternal hemorrhage management.

The timing of delivery should be individualized, depending on patient circumstances and preferences. One option is to perform delivery after fetal pulmonary maturity has been demonstrated by amniocentesis. However, the results of a recent decision analysis suggested that combined maternal and neonatal outcomes are optimized in stable patients with delivery at 34 weeks of gestation without amniocentesis. The decision to administer antenatal corticosteroids and the timing of administration should be individualized.Surgical Details and Preparation

|

| highly vascular lower uterine segment, suggesting placental implantation in the area where an incision would normally be made Image from Cheung and Chan, 2012 |

Most resources strongly recommend against cutting into the placenta at all. This will help minimize bleeding.

If the placenta is low-lying (placenta previa with accreta) or covers most of the anterior wall, doctors may decide to use a vertical (up-down) instead of the usual low horizontal side-to-side incision.

|

| placenta percreta, bladder involvement Image from AJOG 2010 |

In the photo to the left, the uterus has been taken out so the doctors can do a fundal (top of uterus) and posterior (on the back side of the uterus) incision in order to keep the placenta and its bladder invasion intact before the hysterectomy.

During the surgery, some doctors have the mother's legs placed in special stirrups. This might seem strange for a cesarean delivery, but it is a precaution so that both vaginal and abdominal packing can be placed if bleeding is significant.

Antibiotics will be administered just before or right as the surgery is started. Because of the increased risk for infection, accreta patients may also receive additional doses after the surgery, if surgery is prolonged, or if uterus-conserving techniques are chosen. If you are a woman of size, don't forget to discuss the possibility of weight-based antibiotic dosing or extended dosing with your doctor in order to minimize your risk for infection. Post-operatively, probiotics may help promote gut health if you experience gastrointestinal problems from the antibiotics.

Preparing for Blood Loss

Because maternal blood loss is one of the biggest risks associated with accretas, ACOG recommends having strong maternal hemoglobin levels in advance of the surgery.

This can be done with iron pills, with herbal preparations (like Floradix, alfalfa, dandelion roots, nettle leaves, beet roots, etc.), or with food (like red meat, dark meat chicken, eggs, cashews, lentils, molasses, dried fruit, seaweed, leafy greens, pumpkin seeds, etc.). Take iron-rich foods with vitamin C, as this increases absorption strongly. Supplementation with Vitamin B-6 may also be helpful. On the other hand, don't take iron pills or foods with dairy products, caffeine, or antacids, as these inhibit absorption.

Your blood should be typed and matched before surgery, and blood products should be readily available in the O.R. during surgery. The blood blank should also be on call to provide additional units quickly if needed. In some areas, they may also be asked to stock certain additives that may also help if a severe hemorrhage occurs.

ACOG also recommends considering having a way to salvage the mother's own blood loss and return it to her during the surgery.

Because of the risk of massive blood loss, attention should be paid to maternal hemoglobin levels in advance of surgery, if possible. Many patients with placenta accreta require emergency preterm delivery because of the sudden onset of massive hemorrhage. Autologous blood salvage devices have proved safe, and the use of these devices may be a valuable adjunct during the surgery.Sometimes, donating blood ahead of time for yourself is possible, as is using a donation from an adult family member with the same blood type. This is not always possible or optimal, but you can certainly ask your doctor about the possibility. It is not standard protocol at this time, however.

You are quite likely to need a blood transfusion at some point in your recovery if you have a significant accreta. Many women require multiple transfusions. Be prepared for this issue, and for the strong likelihood of hysterectomy if bleeding is not able to be controlled.

Anesthesia

The best anesthesia choice for accreta patients is still debated.

Many OBs strongly prefer general anesthesia. This offers the advantage of an unlimited amount of surgery time (in case the surgery is complicated). It also keeps the patient unconscious during what may be a difficult and scary surgery (most percretas are done with general anesthesia, for example). The biggest disadvantage of a general is that it tends to affect the baby negatively, and doesn't provide very good post-op pain relief.

Some OBs are fine with regional anesthesia (spinal, epidural, or combined spinal-epidural [CSE]). This allows the mother to be conscious for the baby's birth, improves fetal Apgar scores, and tends to offer better post-partum pain control as well. However, most regional anesthesia (except CSE) will not last long enough if surgery becomes prolonged. In addition, most surgeons don't want the patient awake if the surgery gets complicated or if massive hemorrhage occurs.

Some OBs will allow a combination of anesthesia choices when circumstances allow. The mother may start with a spinal or epidural so she can be awake for the baby's birth and so that the baby has minimal exposure to the strong drugs of general anesthesia. Once the baby is delivered and the surgeons have evaluated placental attachment, they may stay with regional anesthesia or opt to convert to general anesthesia so it will work for as long as needed and so that the patient is not awake in case major complications occur.

An anesthesia consult ahead of delivery is very important. You and your care providers should discuss the pros and cons of various approaches, your preferences, and the unique circumstances of your condition that may affect anesthesia choice.

Pre-Operative Precautions

Before a planned cesarean, there are several routine precautions often employed to help improve outcome.

Many providers recommend a special skin preparation routine the day before or the day of the cesarean. This may help reduce the risk for infection, although evidence is not yet clear on the best protocol for skin preparation.

Intravenous access (I.V.) is always placed before any surgery, but your doctors will probably recommend that you have large-bore IV lines or an arterial IV line placed before surgery. This allows a large volume of fluids or blood products to be delivered more quickly in case of hemorrhage.

Many hospitals now use pneumatic compression stockings for all surgical patients. These inflate and deflate on the legs to lower the risk for the development of blood clots that could travel to the lungs. If the standard size does not fit, there are usually pneumatic compression devices that can be used instead of compression stockings. These should be placed before the operation and stay in use until the patient is walking regularly afterwards.

In addition to these procedures, some doctors choose to place a stent (small tube) or catheters in the ureters before a cesarean hysterectomy, which may lessen the risk for damage to the ureters. Again, research is ongoing into this procedure.

Additional Blood Loss Treatment Options

|

| placing arterial catheters (C) and ureteral catheters (U) pre-operatively E is the external fetal monitor Image from Ochsner 2011 |

Some OBs place an internal balloon catheter pre-operatively in the arteries around the uterus so that if severe bleeding does occur, they can inflate the balloon to try and shut down the bleeding. A recent literature review of this procedure found conflicting results and recommended further research.

Doctors can also clamp off the uterine arteries in order to reduce the amount of bleeding during the cesarean. This may not be effective because there are many alternative sources of blood supply to this area, but it is another tool in the arsenal that doctors can consider.

Another option is the afore-mentioned Uterine Artery Embolization (UAE). While UAE is usually done in non-pregnant women to treat fibroids, it can also help lessen bleeding with an accreta, either during a hysterectomy or post-operatively. And, as previously mentioned, it may also be tried in a uterus-conserving management of accreta.

It should be noted that all of these additional procedures are still controversial. ACOG notes:

Current evidence is insufficient to make a firm recommendation on the use of balloon catheter occlusion or embolization to reduce blood loss and improve surgical outcome, but individual situations may warrant their use. Despite initial enthusiasm about the utility of balloon catheter occlusion, available data are unclear regarding its efficacy. Although some investigators have reported reduced blood loss, there have been other reports of no benefits and even of significant complications.Bottom line, no one is sure whether these procedures help more than they harm. Research is ongoing.

Birth Plan

Accreta can have such variable outcomes that it is important to have a plan in place for various potential outcomes. This can help guide your doctors about your wishes if you are not available to consult right away.

Things you might want to consider putting into your plan include guidelines for infant feeding, kangaroo care for your partner, preferences regarding newborn procedures and vaccinations, etc. You might also want to consider requesting milk from a human milk donor bank until you are able to produce your own (which might be delayed due to blood loss or placental fragments left inside).

After the Delivery

You will probably be in the hospital for a longer recovery time than most cesarean mothers. You may experience significant abdominal pain afterwards (more than the normal cesarean pain) because of internal bleeding and the surgical trauma of a difficult operation. Wound healing may be somewhat delayed as your body tries to cope with the demands of such a significant challenge to the system.

One Australian study found that about half of women with accreta developed some sort of surgical complication (usually bladder injury), and about 20% needed to have additional surgical procedures later on. If you develop blood in your urine, this should be evaluated right away. In addition, hidden bleeding and infection may develop afterwards, so be sure to get prompt attention if you start to feel more unwell than usual.

It is very important to support your body nutritionally to help it recover from significant blood loss. Plan on getting plenty of B vitamins and iron after the birth in order to help rebuild your blood supply. Drink plenty of water. Nuts, leafy greens, dried fruit, and red meat are good natural sources of iron, folate, other B vitamins, and the A vitamins so vital to healing.

Long-term, you should be tested several times for postpartum anemia. The majority of women with accreta suffer a quite significant blood loss and this can cause long-lasting anemia. Although many care providers are aware of this, it sometimes gets overlooked as a "minor" concern once the life-threatening crisis is over, and follow-up testing can be neglected. Yet it is a critical quality-of-life issue for your healing and long-term recovery, so don't be hesitant to be assertive about having your levels checked.

Remember that hemorrhage, retained placenta, and anemia can also all negatively negatively impact milk supply, and prematurity can make it difficult for babies to latch on efficiently. Although some women in this situation are able to make breastfeeding work without problems, don't hesitate to consult an IBCLC (Internationally Board-Certified Lactation Consultant) for help if needed.

In time, adequate milk supply may develop with regular pumping, but in the meantime, you may need to supplement with donated human milk or formula while proactively promoting milk supply (see http://www.lowmilksupply.org/). Information about supplementation can be found here. And a great resource for unbiased, non-judgmental support for mothers struggling with breastfeeding difficulties can be found here.

If you experienced a very severe hemorrhage during delivery, be aware that this can sometimes damage your pituitary gland (Sheehan's Syndrome). Thyroid issues, fatigue, body hair loss, and adrenal issues are common long-term complications. If you cannot breastfeed and the return of your period is delayed or quite irregular, ask to be for tested for Sheehan's Syndrome. Also be aware that this complication sometimes doesn't show up until years later, so you may need to be retested several times over the years.

Be sure to plan for a longer recovery time and extra help after the delivery, since recovery is likely to be harder after an accreta. Don't rush your recovery, but take plenty of time to rest and let your body heal slowly. Sleep, good nutrition, and taking your recovery slowly are your best allies in this.

Having a baby is hard enough on the body; dealing with an accreta and blood loss on top of that is even harder. Get extra help around the house (a postpartum doula may be helpful) and be sure to accept the help of friends, extended family, and neighbors as much as circumstances allow. Your job is simply to heal and to take care of the baby. Let your partner and others step up to take care of everything else.

Summary

Placenta Accreta is a rare but very serious complication that is associated with prior uterine instrumentation procedures. Although it can occur after a number of different procedures, it is most strongly associated with prior cesarean. It is most common with rising numbers of prior cesareans, but can occur even in women with only one prior cesarean.

Accretas come in three different levels of severity, but make no mistake, all are potentially life-threatening. Although minor degrees of accreta can often be resolved without major repercussions, the potential for serious complications is always there and must be taken seriously. And the potential complications with the most severe forms are sobering indeed.

Of course, it's only fair to point out that even though the risk for abnormal placentation rises with each cesarean, most women with prior cesareans do not experience placenta previa or accreta. And most cesareans go well, even higher-order cesareans. So if you have had cesareans before, don't panic. Chances are you'll be okay.

However, from a public health point of view, the take-home message is that risks start rising rapidly as the total number of cesareans increase.

Complications like previa and accreta are more common after three to four or more cesareans. However, sometimes these complications happen when a woman has "only" had one or two prior cesareans. Just because you've only had one or two cesareans instead of four doesn't mean you aren't at risk. It all depends on how well your uterus was able to repair itself and exactly where an embryo implants.

And although the absolute risk for previa and accreta overall is low, it's far higher than it is in women who have never had any cesareans.

Don't forget, sometimes there are babies and women who die from placenta accreta/percreta, or have very near misses.

At the very least, it often results in severe hemorrhage, hysterectomy, loss of fertility, uterine rupture, and significant damage to the urological system or abdomen of the mother, not to mention prematurity in the baby.

This is why it is important to avoid the first cesarean whenever possible, to not automatically schedule repeat cesareans in most women, and to make sure that VBAC stays an option for as many women as possible.

Unfortunately, this is the exact opposite of what's happening in many places right now. And that's why the world will continue to see a strong rise in the number of women experiencing placenta accreta and all its complications. As one recent study concluded:

If primary and secondary cesarean rates continue to rise as they have in recent years, by 2020 the cesarean delivery rate will be 56.2%, and there will be an additional 6236 placenta previas, 4504 placenta accretas, and 130 maternal deaths annually...If cesarean rates continue to increase, the annual incidence of placenta previa, placenta accreta, and maternal death will also rise substantially.

This topic is on my mind because an online friend of mine recently faced placenta accreta. She has given me permission to share her story.

She had an excellent OB and surgical team, her accreta didn't look too severe, and she had her surgery at a very good hospital. But she knew that there were no guarantees, that sometimes an accreta that doesn't look major turns out to be more serious. She was uneasy after reading the story of the mother in Utah who died recently due to placenta accreta and worried about leaving her other children behind.

In the end, I'm happy to report that she had an overall "good" outcome. They were able to hold off the cesarean until almost term, so baby was not very premature at all. The mom didn't need to have emergency surgery; they were able to hold off until a very extensive team of surgeons and specialists were standing by, ready to intervene if needed.

Sadly, though, her accreta was severe enough that they did have to do a hysterectomy. Now this mother has lost her uterus and any chance at future children. She also suffered a lot of blood loss, including internal bleeding after the cesarean that left her with a lot of fatigue and very serious and long-lasting pain.

What's so frustrating is that this might have been preventable. Mismanagement by care providers in pregnancies previous to this one led her down this path and that she is angry about.

She is a woman of size who followed the common birth trajectory of many heavier women ─ pressured into an induction because of her providers' fears about postdates and big baby. Like so many in that situation, she ended with a c-section for "failure to progress" with a malpositioned baby. Like about twelve to thirty percent of big moms, she developed an infection and had a rough recovery.

She was promised that she could pursue a VBAC but was given the old bait-and-switch routine at the end of her second pregnancy. Many care providers tell high-BMI women they can have a VBAC and then find some reason at the end why they shouldn't have one after all. They pressured her into a repeat cesarean because they told her she was overdue (she wasn't) and because they feared a big baby (baby was 7 lbs.). So she ended up with a totally unnecessary 2nd c-section.