|

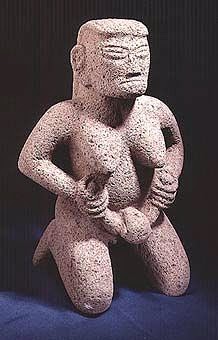

| Birth statue from the Kraja people of the Amazon |

Why do women use these passive positions and not more active positions like upright, kneeling, squatting, all-fours, side-lying, or asymmetric positions, which have historically been favored by many cultures?

Recent research just published shows that these "alternative" positions offer increased room in the pelvis. And many women feel their pain is lessened in these positions. This is probably why they were favored by traditional birthing cultures.

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis shows that labors tended to be shorter, the risk for cesarean was lower, and fewer epidurals were used when women in hospitals labored in these positions. So why aren't more women taking advantage of these positions?

The main reasons are cultural conditioning (nearly every image of birth in the media involves laying down or semi-sitting positions), because freedom of movement can interfere with labor interventions, because epidurals can restrict movement somewhat, and because some medical personnel discourage alternative positions due to lack of training/comfort with them. Sadly, there are some care providers who actually forbid women to assume other positions for pushing out the baby.

Women should be able to choose their position for labor and birth freely and without restriction from their providers, yet this is often not the case, even today.

In future posts, we will discuss institutional and cultural barriers to using alternative birthing positions, research around use of these positions, and ways to bring more of this positioning into the hospital.

But today, let's start by showing standard hospital positions for perspective, then contrast those with illustrations of alternative birth positions from historical artwork. The point is to show the variety of birthing positions used in history and among First Nation peoples today, in contrast to the lack of variety in most hospitals.

For some time, I have been collecting illustrations of birthing positions in various cultures and time periods from around the world. It's been a fascinating and educational process. A list of sources for them is available at the bottom of the post in the References section. Note that there are even some plus-sized images!

Enjoy these inspiring and beautiful images. May they encourage more women to utilize alternative positions, and may they help care providers provide more support for alternative positioning to birthing women everywhere.

In the hospital today, some care providers restrict the mother's position while in labor or while pushing. Many women are required or strongly pressured to lie back or to use a semi-sitting, splayed position with legs raised and pushed back or out. Even when care providers do not specifically restrict birth positions, women still usually end up in positions like the following ones.

This is a "lithotomy" or fully reclined position, with legs splayed strongly apart in stirrups to give the doctor as much access as possible. A "dorsal recumbent" position is basically the same, except that the patient's legs are not in stirrups but are flexed and on the bed.

Laying back tends to compress the major blood vessels leading to the uterus, potentially leading to restricted blood flow to the baby and fetal distress. This is ironic, since for nine months physicians tell women to avoid sleeping on their backs because this can compromise blood flow to the baby. Yet when women arrive in the hospital to birth the baby, the first thing they often do is to put them on their backs!

Most of the time, women give birth these days in the semi-recumbent position, which is basically like a lithotomy position but slightly propped up so the woman is not flat on her back. The knees are splayed widely apart and the legs are either in stirrups, pulled back by the mother, or held up by helpers.

One major issue with the lithotomy and semi-recumbent positions is that not only do they not utilize gravity to use the baby's own weight to help it move down, but they actually make the mother work against gravity in order to push the baby out.

The semi-sitting position came into use in the hospital as a way to get the mother a little bit more upright to make better use of gravity. The position is similar to the semi-recumbent position except that it is just a little bit more upright. However, note that it is not all that upright. Knees are usually splayed and held upright by helpers or the mother, and the back is rounded forward with chin to chest like a "C."

Another problem with all of these positions is that they actually decrease the size of the pelvic outlet. The sacrum is against the bed, making it hard for it to move during labor. The direct pressure on the woman's tailbone forces it upwards in a more curved position and into the pelvic outlet space. Pulling the knees strongly apart tends to narrow the pelvic outlet in the back as well. These give less room for the baby to get out. It also tightens the pelvic floor and may make it more likely to tear.

One survey of U.S. birthing women reported that as recently as 2005 that "57% gave birth lying on their backs and an additional 35% gave birth propped up in a semi-sitting position." In other words, 92% of the women gave birth in either semi-reclining/reclining or semi-sitting positions.

If all those women truly want to give birth in those positions, that's no problem. Some women find them comfortable or useful, and it's perfectly fine to use them if desired. However, many women report wanting to use other positions and being discouraged or even forbidden from using them.

Recent research just published shows that these "alternative" positions offer increased room in the pelvis. And many women feel their pain is lessened in these positions. This is probably why they were favored by traditional birthing cultures.

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis shows that labors tended to be shorter, the risk for cesarean was lower, and fewer epidurals were used when women in hospitals labored in these positions. So why aren't more women taking advantage of these positions?

The main reasons are cultural conditioning (nearly every image of birth in the media involves laying down or semi-sitting positions), because freedom of movement can interfere with labor interventions, because epidurals can restrict movement somewhat, and because some medical personnel discourage alternative positions due to lack of training/comfort with them. Sadly, there are some care providers who actually forbid women to assume other positions for pushing out the baby.

Women should be able to choose their position for labor and birth freely and without restriction from their providers, yet this is often not the case, even today.

In future posts, we will discuss institutional and cultural barriers to using alternative birthing positions, research around use of these positions, and ways to bring more of this positioning into the hospital.

But today, let's start by showing standard hospital positions for perspective, then contrast those with illustrations of alternative birth positions from historical artwork. The point is to show the variety of birthing positions used in history and among First Nation peoples today, in contrast to the lack of variety in most hospitals.

For some time, I have been collecting illustrations of birthing positions in various cultures and time periods from around the world. It's been a fascinating and educational process. A list of sources for them is available at the bottom of the post in the References section. Note that there are even some plus-sized images!

Enjoy these inspiring and beautiful images. May they encourage more women to utilize alternative positions, and may they help care providers provide more support for alternative positioning to birthing women everywhere.

NSFW Warning: Birthing pictures tend to be graphic. Proceed at your own discretion.Modern Institutional Birth Positions

In the hospital today, some care providers restrict the mother's position while in labor or while pushing. Many women are required or strongly pressured to lie back or to use a semi-sitting, splayed position with legs raised and pushed back or out. Even when care providers do not specifically restrict birth positions, women still usually end up in positions like the following ones.

|

| The "lithotomy" position, legs in stirrups |

Laying back tends to compress the major blood vessels leading to the uterus, potentially leading to restricted blood flow to the baby and fetal distress. This is ironic, since for nine months physicians tell women to avoid sleeping on their backs because this can compromise blood flow to the baby. Yet when women arrive in the hospital to birth the baby, the first thing they often do is to put them on their backs!

|

| A semi-recumbent position, very similar to lithotomy but the back is propped up somewhat |

One major issue with the lithotomy and semi-recumbent positions is that not only do they not utilize gravity to use the baby's own weight to help it move down, but they actually make the mother work against gravity in order to push the baby out.

|

| The Semi-Sitting (or Semi-Fowler's) Position, with the mother propped up at about a 45 degree angle |

Another problem with all of these positions is that they actually decrease the size of the pelvic outlet. The sacrum is against the bed, making it hard for it to move during labor. The direct pressure on the woman's tailbone forces it upwards in a more curved position and into the pelvic outlet space. Pulling the knees strongly apart tends to narrow the pelvic outlet in the back as well. These give less room for the baby to get out. It also tightens the pelvic floor and may make it more likely to tear.

If all those women truly want to give birth in those positions, that's no problem. Some women find them comfortable or useful, and it's perfectly fine to use them if desired. However, many women report wanting to use other positions and being discouraged or even forbidden from using them.

Historic Birth Positions

Although most women envision birth in a semi-reclining or semi-sitting position these days, there are many other possible positions in which to give birth.

However, it's always important to point out that there is no one "right" position for laboring or pushing out a baby. All positions have pros and cons.

Care providers should encourage women to experiment with different positions and then trust that the woman's body will tell her the right position for her needs. If a woman is not making progress with a certain position, encourage her to try other positions, as these may help the baby move down or turn to help labor progress, but in the end it is the mother who should have the ultimate say in her position.

If the traditional semi-reclining or semi-sitting positions feel "right" to you, there is nothing wrong with that. Many babies have been born that way just fine. If you like that position and your baby is well-positioned and descending just fine, there is no need to alter that.

However, many women want to move into other positions in labor and while pushing, or their babies are not descending well in the usual positions and might benefit from a position change ─ yet they are often actively discouraged from changing positions. This is short-sighted because it does not heed the physics of pelvic structure (the extra room for fetal descent in different positions) or the maternal pain relief that different positions can bring.

In non-Western countries (and outside the hospital in Western countries), many women give birth in so-called "alternative" positions, like squatting, standing, semi-squatting, kneeling, asymmetric (one leg up and one down), all-fours, back arched, or side-lying.

While you can find pictures of all birthing positions (including reclining) in ancient art, most art from ancient cultures did not show women birthing while lying down.

This is a strong statement about the differences in birthing culture then and now. Most likely there is a strong physiological reason why most of these women did not birth lying down.

Let's review a few of these "alternative" positions.

Squatting

Check out this peaceful Filipino woman, also giving birth in a full squatting position (art credit: Alicdang of Sagada).

Many tribal societies, from Native Americans to African tribes, have illustrations or statues of women squatting to give birth, like this pottery illustration from the Mimbres Pueblo tribe. Notice that the mother's knees are far apart.

In this Egyptian carving, the woman is squatting to push, while bracing herself on helpers and furniture of some sort. Notice her knees are closer together than in the other pictures. Many childbirth educators have observed that the back half of the pelvic outlet in the squatting position actually increases more when the knees are a bit closer together than farther apart.

This classic birth statue of an Aztec goddess pushing out her baby while squatting seems to reflect that. Her knees are not widely spread. Her face certainly shows the intensity of pushing!

Regardless of whether the knees are far apart or not, squatting is a position that is shown in a great deal of artwork from ancient or traditional societies, as in this illustration of a birthing woman from the Tonkawa Indian tribe of North America.

Supported Squatting

Some women find squatting too tiring to sustain during birth. Many utilize what is called a "Supported Squat" position instead. The most common way to help sustain a squat is to lean on something or to hold onto other people, one on each side.

In this South Indian carving, for example, a woman gives birth in a standing squat, holding on to women on each side of her. The midwife's size below shows her relative unimportance in the artist's mind compared to the mother. Notice that the mother is shown as the largest and most powerful figure in the carving, probably as a commentary on the power of the birthing woman.

In this ancient Greek relief, a woman is shown squatting on a birth stool with arms around helpers on each side while the midwife catches the baby from below.

In this carving from ancient Egypt, the mother also gives birth while holding onto attendants on either side. She uses a stool for stability but her position is very much a supported squat.

Kneeling

A position very similar to squatting is kneeling. Birth art from many different cultures depicts kneeling for birth, either on both knees or asymmetrically with one knee up and one knee down.

Basically it's pretty close to squatting in many ways, except the mother is on her knees instead of her feet, and she is fairly close to the ground, as in this statue from Costa Rica.

Many Egyptian carvings show women giving birth in a kneeling position, like this one.

This illustration of a kneeling position, supposedly of Cleopatra, is also from Ancient Egypt. Notice that she is being helped to hold her arms up to give her some counter-force (more on that later).

It's difficult to tell the birth position in this Japanese illustration, but it certainly looks like she is kneeling.

And this pre-Columbian Jalisco statue also appears to use a kneeling position.

So does this statue from the Kraja people of the Amazon...

...and this African statue from Cameroon.

Many First Nation peoples from North America used kneeling positions for birth. This Inuit statue shows a mother and her birth support person behind her, both kneeling.

In this illustration of a kneeling position of the Blackfoot Indian tribe of North America, the woman uses a pole in the ground to help give her support while kneeling.

In this woodcut illustration of the birthing practices of the Comanche tribe, a series of poles were driven into the ground, outside a circular temporary shelter. The woman in labor would walk back and forth along this line of poles, kneeling and leaning forward onto a pole during contractions. Her labor support person would massage or give quick shaking motions to her belly during contractions (this is rumored to help encourage babies into more optimal positions for birth).

Sometimes she would go into the privacy of the shelter and squat over holes with hot stones (heat can be comforting in labor) and aromatic herbs. She might have given birth in any of these spots but she likely was in a kneeling or squatting position when she did give birth.

Hands and Knees Positions

Another position that was popular was a variation of the kneeling position. Today we call this the all-fours or hands-and-knees position, although the mother wasn't always completely on her hands and knees.

For example, in this illustration of an 1800s African-American woman from the American South, the mother labors while kneeling on the floor but leaning on a chair so she could rock back and forth during labor. Notice that the position of her legs is a bit asymmetrical.

A hands-and-knees position is different than the upright kneeling positions seen in the kneeling illustrations in the previous section. The hands-and-knees position is not an upright position, but rather a kneeling one with the mother at a significantly inclined angle.

Here is a Persian woman, using stones to help her assume an elevated variation of a position somewhere between the all-fours position and the supported squat.

In this small section of a larger painting from a temple in Bhutan, the mother gives birth on her knees and elbows (sometimes called a knee-chest position). This can be a particularly good position for a mother who is experiencing a really painful back labor.

Upright Sitting

A lot of ancient birth art showed women in a mostly upright, semi-squatting/semi-sitting pose, such as in this Roman carving. Note the position is far more upright than traditional Western semi-sitting positions.

Here is an illustration of a sitting position from a Tibetan temple. Notice how upright the mother is, even as the baby is coming out.

In this statue from Burkina Faso from Africa, the mother is sitting, but she is mostly upright. Notice that this baby is even coming out breech (not head-first)!

Semi-Reclined

Of course, some positions were more than a little reclined. They were usually not flat on their back like a lithotomy position, mind, but were a bit more recumbent than those above.

Here is an illustration from a Persian mirror case. The mother is a little more reclined in this one, but is not totally reclined either.

Here is a semi-reclined position from some Mexican pottery.

This statue from Costa Rica also is semi-recumbent, but without abducting the legs so far apart and elevated, like hospital positions often are. The back also looks a little arched (see below).

Here is a similar statue from Ecuador. Again, notice the more natural position of the legs, rather than having them lifted and strongly abducted.

Reclining

Although it is harder to find historical artwork of women giving birth in a very reclined position, there are some records of that position too.

This Cameroon woman from Africa is giving birth fully reclined on a "maternity couch."

This illustration is of a French Canadian woman propped up in a mostly reclining position on a mattress over an upside-down chair. Notice, though, that her knees are not splayed or pushed back.

Note that even though semi-sitting, semi-recumbent, and reclining postures were seen among older cultures, there were some important differences to the ones seen in many hospitals now. Their semi-sitting positions were often more upright than ours, and when they laid back, their legs were not usually as elevated and splayed as they are in most semi-recumbent and recumbent hospital positions today.

Asymmetric Positions

Another variation on these positions is the asymmetric position.

Having each leg on a different level (whether during a semi-sitting, reclining, kneeling, or all-fours position) makes one side of the pelvis higher than the other. This opens the pelvis on one side, making more room for a baby to turn from a less-than-optimal position. This can be a powerful tool in a non-progressive labor.

Here is a painting, possibly from Finland, showing the woman sitting near the edge of a bed or stool. At first it looks like the usual semi-leaning back position. However, notice that one leg is up on a stool while the other is down. This makes it an asymmetric position.

This Indian painting shows a reclined woman giving birth on a bed, though her head is raised a bit. Notice that one of her legs is propped on the midwife's shoulder while the other is down, giving her an asymmetric position while lying down.

Many women who give birth quickly or unattended assume an asymmetric position naturally. This woman from Mexico assumed an asymmetric position (one leg up and the other leg down) instinctively in a recent U.K. birth that occurred so fast she gave birth on the lawn outside the clinic.

Birth Stools

Many women over time have used a a birth stool, as in the Ancient Greek carving above, because birth stools allow women to stand, squat, or semi-squat while actively pushing, then to sit back and relax between contractions.

If the mother stays seated the whole time she is pushing out the baby, a birth stool has the same disadvantages of the semi-sitting position (pushing the tailbone into the pelvic outlet and making it smaller). However, if the mother uses it to give support between shifting positions, it combines the best advantages of both the sitting and squatting positions.

|

| Birth stool from about 1580 |

Here is an illustration of a birth stool in use in Europe about 1580. The use of a birth stool was extremely common in many European cultures.

Here is another birth stool birth from Europe, about the same time period, and the mother is even plus-sized!

Birth stools of various sorts have been very popular throughout history. Sometimes the care provider would bring the birthing stool with them to births....

...while other birth stools were family heirlooms, handed down through the family.

Often birth stools were close to the floor and without arms, but sometimes they were full-on chairs with backs, sides, and footrests, as in this European illustration.

Each type of birth stool has advantages and disadvantages, and some midwives and doctors had birth stools custom-made for them based on their preferences.

|

| Image from the Wellcome Trust of the U.K. |

In this more recent Greek illustration, a woman is held by her husband on a birthing stool, while the midwife crouches before them on a low stool.

There are many, many other illustrations of births on birth stools available. In the interests of space I will not post them all, but if you are interested you can find many additional images.

If you didn't have a birth stool, sometimes you improvised your own version. Lap-sitting on someone's lap was another very popular alternative, as shown here in an early American illustration. This position was very common among the settlers along the frontier.

The husband sat on a chair, and another chair was placed on its front on the floor in front of the first chair to support the mother. This created a sort of poor woman's birth stool. (Alternatively, a sheet was placed over the husband's lap to create a sling for the mother to sit on.) The birth attendant sat on a smaller improvised stool in front of the mother. The husband helped support the mother as she shifted between semi-sitting, semi-squatting, and standing positions.

Standing Positions

Standing and walking during labor is extremely common in many cultures, but women often shifted position for the actual final pushing out of the baby. However, birth while standing up did happen at times too.

For example, in this illustration of a birth scene from the Western African tribe of the Wakambas, the mother gives birth standing up, attended by 3 other women.

In this relief carving from India, the mother is assisted to birth in a standing position by helpers on either side.

In this image from Angola in Africa, the mother is shown giving birth standing. (Statues in certain African cultures were often given elongated forms.)

In this illustration of the Kiowa Indian tribe from the North American plains, a helper in front blows into the mouth of a mother standing to birth, while the midwife catches the baby from behind. It is not clear what the blowing is for, but probably was used as a focus or distraction technique, to help with breathing techniques for pain relief, or as a symbolic "blowing in" of strength.

Here is a similar scene from the Sioux Indians [some sources list it as being from the Iroquois]. The woman holds onto someone in front in a half-standing/half supported-squat while the midwife catches the baby from behind. Some accounts say that the tall supporter role in front was often given to a young bachelor male of the tribe, rather than the father. Presumably this was so that the father could see his baby be born, and so that young men developed an understanding of the potential consequences of sex!

Positions Using Counter-Force

Many women over time have found that having something to actively pull or push against while birthing the baby was helpful. Thus many traditional birth positions combined squatting, birth stools, kneeling, standing, or other positions with a way to let the mother utilize a counter-force.

For example, as this "Pioneer Birth Scene" illustration shows, women would often sit on their husband's lap to imitate a birth stool, half-stand or pull against someone in front of them during a contraction, then lean back and rest on their husband between contractions.

Some cultures used a rope tied to a tree or a cloth tied to something, as in the above illustration of an African American woman from the South. This helped the woman to be in a standing squat position. The rope helped support her weight so her legs wouldn't get as tired.

Here is a Sioux Indian woman from North America, using a rope tied around a tree to pull against for sideways counter-force.

In this illustration of Oronoko Indians from South America, the woman uses a sling and her helper to help support her semi-standing, semi-dangling squat position.

Here is another illustration of a dangling position, this time using a rope to help the woman relieve the pressure in a kneeling position. In this illustration of a scene from Mexico, the labor helpers are using their hands to massage and shake the woman to try to reposition the baby during a difficult labor.

This South Indian carving also shows the mother putting one hand down on a support and the other hand pulling on a vine or some sort of rope to birth her baby in a supported squat position.

Sometimes pushing away from something feels better. In this carving from Peru, the mother sits back against someone in the semi-squatting position. In that way, she can lean back and use counter-force the other way.

In this illustration of the birth traditions of the North American Pawnee tribe, the mother leans back and pushes against someone else while in the squatting position. The person behind her provides both stability and something to push against when needed. [Again, blowing on the mother seems to be part of the tradition of some Plains Indians. Aromatic smoke to the belly or perineum was used by several other indigenous peoples.]

In this Andamanese labor scene, the woman is in a supported semi-sitting position, but she uses her feet to push against a wall for more leverage. [The Andamese were a tribal people who lived on the small islands between India and Burma. They are nearly extinct now.]

Some cultures used a stick to dangle from, as in the illustration from Mexico above and also this African illustration from Angola. In this one, the mother stands with her back pushing against a tree, and also dangles from a stick placed at an angle to the tree. In this way, she gets counter-force both from behind and above.

Arched Back

Dr. George Engelmann, a physician who wrote a book in 1884 about birthing practices around the world (from which many of these illustrations are taken), notes that dangling or upright kneeling positions were common among many tribal peoples, and nearly always involved a change in the direction of the body's axis as the birth neared.

In other words, many women changed from leaning backwards to leaning forwards, or from leaning forwards to leaning back. This probably helped work the baby down through the pelvis or created more room for the cardinal movements of birth (turns and twists a baby must make to successfully navigate through the pelvis).

|

| The Semi-Sitting Position in the hospital. Note the mother is encouraged to curl forward into a "C" position |

Yet many women instinctively try to change their axis and arch their backs in the opposition direction instead, especially at the last moment as they are pushing the baby out. Historical art shows several examples of this instinct.

Notice that in this statue from the Congo, the woman is in the common semi-sitting position, but she is arching her back strongly. As noted, in the hospital this is often discouraged and women are told to curl forward instead..all with the best of intentions. Yet arching the back may help move the sacrum and tailbone out of the way, tilt the public symphysis, and help create more space for the baby to move or for the shoulders to turn when needed.

In this variation on the Aztec squatting statue from above, note that the mother throws her head back and seems to have more of a slight arch to her back than a rounded forward back like hospitals recommend.

If you look closely, this ancient Cyprus birthing scene shows the mother lying back and arching her back somewhat. Certainly she is not curled forward into a "C" position. Although this is right after the birth of the baby and she could just be lying back to rest, her position suggests that this is how she actually pushed out the baby.

Sometimes women get in some seemingly strange positions while pushing, as in this Italian illustration. Lying back and dangling the legs over the side of the bed is one of these, but in some obstetric texts this position was listed as another remedy for shoulder dystocia (where the shoulders get stuck).

In the above and below illustrations, this extreme position was recommended especially for "corpulent" women as a way to get the weight of the abdomen off of the uterus and birth canal, an old variation on the "fat vagina" theory we still hear spouted today. <insert eye roll>

Obviously, take that one with a grain of salt. Women of size successfully give birth vaginally in many positions, and many women of different sizes try to arch their backs as they are expelling the baby. Likely there is more to it than such simplistic stereotypes.

However, that doesn't mean that this position is not potentially useful for other birth situations. In fact, a German doctor named Gustav Walcher described a similar position over a century ago. The website, Spinning Babies, has a whole page devoted to Walcher's Position, with several illustrations and historical details.

In Walcher's Position, the woman is scooted to the edge of a high bed, arches her back, and lets her legs passively hang over the edge of the bed and dangle. If a high-enough bed is not available, extra cushions or a trochanter roll (such as those used in yoga or massage) are put under her hips to create the needed angle of arch. This is supposed to be an excellent position for helping a high baby engage into the pelvis and to open up the pelvic brim. They also note that the position is sometimes used for breech births or for resolving shoulder dystocia.

Something similar to this position seems to be suggested by this carving of childbirth from Peru. Notice the angle of the mother.

I have heard OB nurses note that many women in modern hospital births try to lift their bottoms off the bed and/or arch backwards a bit, especially at the last minute as the baby is about to come out.

|

| Page 142 from Dr. Engelmann's book |

This may well be a woman instinctively trying to get the sacrum and tailbone out of the way at the last minute so the baby can come out more easily. Sadly, many hospitals actively discourage this back-arching movement. They mean well, believing arching back inhibits the baby negotiating the pelvis properly, but this ignores the fact that not every woman is alike and some may have a unique pelvic structure that benefits from an arched back at some point. Some may need the extra room that getting off the tailbone provides; others may simply find that the arched back position offers less discomfort.

It's one thing to encourage a rounded back and forward-leaning posture because that may help most babies engage or move down better in general, but it's another to discourage or forbid a back-arching movement to women whose bodies are telling them that they need to do this. Care providers need to trust more in women's instinctive moves in labor instead of imposing one way of doing things. If a woman feels she needs to arch her back in labor or pushing, she should give it a try and see if it is helpful. The proof is in the results; if it doesn't help she can always go back to the "C" position.

[This is a personal pet peeve for me because arching the back is what my body wanted to do with my third baby. The nurses (who were very nice and who meant well) prevented me from leaning back and arching my back. They forced me instead into a "C" position. I made NO progress in that position. When I finally leaned back and arched my back despite them, the baby came very quickly. Moral of the story: If the mother's body is telling her to move a certain way while pushing out the baby, there's probably a good reason for that!]

Side-Lying

An excellent alternative position if the mother is tired or feels more comfortable lying down is the side-lying or lateral position. The mother's top leg can be abducted and propped up by a helper or squat bar, or rolled far over the other to create a kind of asymmetric position (called a Sim's position in modern obstetric literature). In this way, pressure on the sacrum and tailbone can be avoided, room in the pelvis can be maximized, yet the mother can still rest lying down between contractions.

This painting of a sidelying position is from a Buddhist temple painting in Bhutan. Notice how one leg is thrown very far over the other to create a more asymmetric position and almost an all-fours position.

Interestingly, this position is not seen often in ancient birth art, but it was used. Dr. Engelmann notes that many Nez Perce Indian women assumed a side-lying position for pushing out the baby, although they usually squatted or stood for labor.

The sidelying position has also been documented at times among the Laguna Pueblo Indians of New Mexico and the Kootenai Indians of the Pacific Northwest in North America.

It is one of the few alternative positions that is well-accepted and regularly utilized in the hospital, especially in women with epidurals. There is good research showing advantages to this position in hospital settings.

Videos of Traditional Birthing Positions

Here are two videos of ancient art demonstrating various traditional birth positions. You will see some of the images above in the videos, but you will see others as well.

Here is another video with more images from various sources, including Native Americans and pioneers in the U.S., as well as tribal peoples from Africa and other areas.

Summary

Artwork from the past and from traditional cultures shows that women historically gave birth in a wider variety of positions than the usual lithotomy, semi-reclining, or semi-sitting positions that most hospital births use today.

Happily, many care providers have developed more flexibility about positions in labor these days, yet research shows that the majority of American women are not actually pushing out the baby in them.

Instead, during pushing, most women are pressured to be on their backs in the "stranded beetle" lithotomy position, or forced to curl forward in a semi-sitting C position, reducing the room available in the pelvic outlet. They are strongly directed to engage in forceful "purple pushing" that often bursts capillaries in the eyes, exhausts the mother, and reduces oxygen levels to the baby. This is not good for either mother or baby. Alternative birth positions and less directed pushing offers the advantage of a more physiological and effective pushing.

Of course, the point must be made that just because traditional cultures used alternative birthing positions doesn't automatically make those positions better. Many questionable and even harmful practices were used across a variety of cultures and time periods; older or "traditional" doesn't necessarily mean better. It is important to subject traditional practices to research to see if they are beneficial or not.

However, a fair amount of research suggests that there ARE significant benefits to upright, sidelying, kneeling, squatting, or other alternative positioning, both during the first stage of labor and during pushing. (Some references below; more on this research in future posts in the series.)

It's very telling that when a woman is given the freedom to move in labor and is not told what position to use, she often moves into these alternative positions. And as Dr. Engelmann noted, even women laboring while lying down will often instinctively try to alter their position near the end of labor by raising up, arching their back or lifting their bottoms, or otherwise altering the axis of their bodies.

Many birth attendants can testify that some non-progressive labors suddenly get "unstuck" and progress quickly once the mother is able to move freely in birth. What may seem like random or counter-productive movements to the observer may actually be just what the mother needs to free up a shoulder or help a baby finish turning to an easier position for birth.

Dr. Engelmann tells a story much like this in his book. On page 73, he recounts a story from another physician:

But this lovely (if dated) film normalizes one alternative position for giving birth, and this is something that more people need to see. As a bonus, it also has a larger mom giving birth squatting without interference just fine, showing that plus-sized mamas can birth vaginally too ─ without having to be flat on their backs with their legs hanging over the side of the bed!

[Be aware that this film contains extreme close-ups of both birth and placentas afterwards. Some people are culturally conditioned to see non-sexual images of women's bodies doing what they are biologically programmed to do ─ give birth ─ disturbing. Don't watch if this would bother you. On the other hand, perhaps it's time to challenge your cultural conditioning!]

In the end, it's important to reiterate that there is no "right" position for birth.

You don't get extra points for having birthed while squatting or standing up. If the usual hospital positions work well for you, that's just fine. But many women find they have less pain, feel more in control, need less pain medication or other interventions, and give birth more easily in some of these alternative positions. All women should have the option of using them, and care providers should be more encouraging of them in the hospital.

The position in which we give birth is very influenced by our cultural conditioning. But when we truly listen to our bodies' instinctive needs, we often naturally assume the position that is needed most for that particular birth.

On the other hand, sometimes we need encouragement to try a different position in labor or birth, and a doula (professional labor support person) can be a wonderful source of ideas and inspiration for this. One consistent image seen in the artwork of many societies is that of the birth helper who assists the mother in her labor position while the midwife or doctor catches the baby. Bring that wisdom from ancient societies into your own modern-day labor ─ use the nurse, a doula, your partner, or a relative to help encourage you to try different positions.

While pregnant, take time to "practice" labor in many different positions. If you haven't tried the position during pregnancy, chances are you won't try it during birth, especially at the hospital where we are culturally conditioned to be in bed. Schedule a "Labor Rehearsal" and try different positions on to see how they feel in your body. This will give your body a somatic vocabulary and kinesthetic memory of different position possibilities that you can try during labor.

Once in labor, trust in your body's ability to tell you what you need. Try different positions and adjust as needed. Listen to the dictates of your body but also be willing to try ideas from others to see what works best for you. In the end, though, remember that you are the ultimate authority of what works best for your body and baby.

Your body was made to birth a baby, but using different positions during labor and pushing may help that process out considerably.

References

Artwork from the past and from traditional cultures shows that women historically gave birth in a wider variety of positions than the usual lithotomy, semi-reclining, or semi-sitting positions that most hospital births use today.

Happily, many care providers have developed more flexibility about positions in labor these days, yet research shows that the majority of American women are not actually pushing out the baby in them.

Instead, during pushing, most women are pressured to be on their backs in the "stranded beetle" lithotomy position, or forced to curl forward in a semi-sitting C position, reducing the room available in the pelvic outlet. They are strongly directed to engage in forceful "purple pushing" that often bursts capillaries in the eyes, exhausts the mother, and reduces oxygen levels to the baby. This is not good for either mother or baby. Alternative birth positions and less directed pushing offers the advantage of a more physiological and effective pushing.

Of course, the point must be made that just because traditional cultures used alternative birthing positions doesn't automatically make those positions better. Many questionable and even harmful practices were used across a variety of cultures and time periods; older or "traditional" doesn't necessarily mean better. It is important to subject traditional practices to research to see if they are beneficial or not.

However, a fair amount of research suggests that there ARE significant benefits to upright, sidelying, kneeling, squatting, or other alternative positioning, both during the first stage of labor and during pushing. (Some references below; more on this research in future posts in the series.)

It's very telling that when a woman is given the freedom to move in labor and is not told what position to use, she often moves into these alternative positions. And as Dr. Engelmann noted, even women laboring while lying down will often instinctively try to alter their position near the end of labor by raising up, arching their back or lifting their bottoms, or otherwise altering the axis of their bodies.

Many birth attendants can testify that some non-progressive labors suddenly get "unstuck" and progress quickly once the mother is able to move freely in birth. What may seem like random or counter-productive movements to the observer may actually be just what the mother needs to free up a shoulder or help a baby finish turning to an easier position for birth.

Dr. Engelmann tells a story much like this in his book. On page 73, he recounts a story from another physician:

…he tells me of attending a lady of good position in society in two labors. ‘In her first labor, delivery was retarded without apparent cause. There was nothing like impaction, or inertia, yet the head did not advance. At every pain she made violent efforts, and would bring her chest forward. I had determined to use the forceps, but just then, in one of the violent pains, she raised herself up in bed and assumed a squatting position, when the most magic effect was produced. It seemed to aid in completing delivery in the most remarkable manner, as the head advanced rapidly, and she soon expelled the child by what appeared to be one prolonged attack of pain. In subsequent parturition [childbirth], labor appeared extremely painful and retarded in the same manner; I allowed her to take the same position as I had remembered her former labor, and she was delivered at once squatting.'I can't end this post without including the beautiful Brazilian film, Birth in the Squatting Position. This doesn't mean that I think squatting is the best way to give birth; some people like to use it, some don't. I think you should move around and find whatever position most suits you ─ and that position may change from birth to birth, depending on the position of the baby.

But this lovely (if dated) film normalizes one alternative position for giving birth, and this is something that more people need to see. As a bonus, it also has a larger mom giving birth squatting without interference just fine, showing that plus-sized mamas can birth vaginally too ─ without having to be flat on their backs with their legs hanging over the side of the bed!

[Be aware that this film contains extreme close-ups of both birth and placentas afterwards. Some people are culturally conditioned to see non-sexual images of women's bodies doing what they are biologically programmed to do ─ give birth ─ disturbing. Don't watch if this would bother you. On the other hand, perhaps it's time to challenge your cultural conditioning!]

In the end, it's important to reiterate that there is no "right" position for birth.

You don't get extra points for having birthed while squatting or standing up. If the usual hospital positions work well for you, that's just fine. But many women find they have less pain, feel more in control, need less pain medication or other interventions, and give birth more easily in some of these alternative positions. All women should have the option of using them, and care providers should be more encouraging of them in the hospital.

The position in which we give birth is very influenced by our cultural conditioning. But when we truly listen to our bodies' instinctive needs, we often naturally assume the position that is needed most for that particular birth.

On the other hand, sometimes we need encouragement to try a different position in labor or birth, and a doula (professional labor support person) can be a wonderful source of ideas and inspiration for this. One consistent image seen in the artwork of many societies is that of the birth helper who assists the mother in her labor position while the midwife or doctor catches the baby. Bring that wisdom from ancient societies into your own modern-day labor ─ use the nurse, a doula, your partner, or a relative to help encourage you to try different positions.

While pregnant, take time to "practice" labor in many different positions. If you haven't tried the position during pregnancy, chances are you won't try it during birth, especially at the hospital where we are culturally conditioned to be in bed. Schedule a "Labor Rehearsal" and try different positions on to see how they feel in your body. This will give your body a somatic vocabulary and kinesthetic memory of different position possibilities that you can try during labor.

Once in labor, trust in your body's ability to tell you what you need. Try different positions and adjust as needed. Listen to the dictates of your body but also be willing to try ideas from others to see what works best for you. In the end, though, remember that you are the ultimate authority of what works best for your body and baby.

Your body was made to birth a baby, but using different positions during labor and pushing may help that process out considerably.

References

**Most of the illustrations above are taken from the following resources. [Be aware that these books are products of their times and contain outdated attitudes and language]

- The 1882 book, "Labor Among Primitive Peoples," by Dr. George Engelmann

- The illustrations by Georges Devy in "A History of Childbirth of All the People" by G. J. Witkowski (1887) [see the National Library of Medicine website]

- This collection of birth art by Janet Ashford

- The Art and Pregnancy website, http://art-and-pregnancy.com/index.php?lang=en

- Wikimedia Commons, Childbirth page

- Wellcome Trust images from the U.K.

- Images from the History of Medicine at the U.S. National History of Medicine archive

- Images from the British Library

- Hospital positions are taken from several sources, including this page.

Evidence Summaries on Birth Positions

- http://evidencebasedbirth.com/what-is-the-evidence-for-pushing-positions/ - good evidence-based summary about birth positions for the pushing phase

- http://themisadventuresofastudentmidwife.blogspot.com/2011/06/birth.html - thoughtful and excellent essay from a student midwife on "Birth: A Technology of Gender" about internalized gender roles and how it influences modern childbirth (including birth positions)

- http://www.birthspirit.co.nz/the-obstetric-bed-resistance-in-action/ - good discussion of birth position and how it influences pelvic dimensions, with many references to medical literature

Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Dec;211(6):662.e1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.029. Epub 2014 Jun 17. Does pregnancy and/or shifting positions create more room in a woman's pelvis? Reitter A1, Daviss BA2, Bisits A3, Schollenberger A4, Vogl T4, Herrmann E5, Louwen F6, Zangos S4. PMID: 24949546

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of different positions on pelvic diameters by comparing pregnant and nonpregnant women who assumed a dorsal supine and kneeling squat position. STUDY DESIGN: In this cohort study from a tertiary referral center in Germany, we enrolled 50 pregnant women and 50 nonpregnant women. Pelvic measurements were obtained with obstetric magnetic resonance imaging pelvimetry with the use of a 1.5-T scanner. We compared measurements of the depth (anteroposterior (AP) and width (transverse diameters) of the pelvis between the 2 positions. RESULTS: The most striking finding was a significant 0.9-1.9 cm increase (7-15%) in the average transverse diameters in the kneeling squat position in both pregnant and nonpregnant groups...CONCLUSION: A kneeling squat position significantly increases the bony transverse and anteroposterior dimension in the mid pelvic plane and the pelvic outlet. Because this indicates that pelvic diameters change when women change positions, the potential for facilitation of delivery of the fetal head suggests further research that will compare maternal delivery positions is warranted.AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002 Oct;179(4):1063-7. MR obstetric pelvimetry: effect of birthing position on pelvic bony dimensions. Michel SC1, Rake A, Treiber K, Seifert B, Chaoui R, Huch R, Marincek B, Kubik-Huch RA. PMID: 12239066

OBJECTIVE: The aim of our study was to measure the impact of supine and upright birthing positions on MR pelvimetric dimensions. MATERIALS AND METHODS: MR pelvimetry was performed in 35 nonpregnant female volunteers in an open 0.5-T MR imaging system with patients in the supine, hand-to-knee, and squatting positions. The obstetric conjugate; sagittal outlet; and interspinous, intertuberous, and transverse diameters were compared among positions...CONCLUSION: An upright birthing position significantly expands female pelvic bony dimensions, suggesting facilitation of labor and delivery.Historical Perspective on Maternal Positions in Labor and Pushing

Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000 Oct;92(2):273-7. Maternal posture in labour. Gupta JK1, Nikodem C. PMID: 10996693

The position adopted naturally by women during birth has been described as early as 1882 by Engelmann. He observed that primitive woman, not influenced by Western conventions would try to avoid the dorsal position and was allowed to change position as and when she wished. Different upright positions could be achieved using posts, slung hammock, furniture, holding on to a rope, knotted piece of cloth, or the woman could kneel, crouch, or squat using bricks, stones, a pile of sand, or a birth stool. Today the majority of women in Western societies deliver in a dorsal, semi-recumbent or lithotomy position. It is claimed that the dorsal position enables the midwife/obstetrician to monitor the fetus better and thus to ensure a safe birth. This paper examines the historical background of the different positions used and its evolution throughout the decades. We have reviewed the available evidence about the effectiveness, benefits and possible disadvantages for the use of different positions during the first and second stage of labour.Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982 Sep;89(9):712-5. The rationale of primitive delivery positions. Russell JG. PMID: 7052116, abstract here.

SUMMARY: Women throughout the ages preferred to be delivered with their trunks vertical and most delivery positions illustrated in historical texts indicate that an upright posture with abducted thighs has been the rule. There is evidence that such a position considerably increases the outlet measurement of the pelvis. Primitive delivery positions often accentuate the mechanical forces usually acting on the pelvis.Research Reviews on Maternal Position for Labor and Birth

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Oct 9;10:CD003934. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003934.pub4. Maternal positions and mobility during first stage labour. Lawrence A1, Lewis L, Hofmeyr GJ, Styles C. PMID: 24105444

BACKGROUND: It is more common for women in both high- and low-income countries giving birth in health facilities, to labour in bed. There is no evidence that this is associated with any advantage for women or babies, although it may be more convenient for staff. Observational studies have suggested that if women lie on their backs during labour this may have adverse effects on uterine contractions and impede progress in labour, and in some women reduce placental blood flow...Results should be interpreted with caution as the methodological quality of the 25 included trials (5218 women) was variable....AUTHORS' CONCLUSIONS: There is clear and important evidence that walking and upright positions in the first stage of labour reduces the duration of labour, the risk of caesarean birth, the need for epidural, and does not seem to be associated with increased intervention or negative effects on mothers' and babies' well being. Given the great heterogeneity and high performance bias of study situations, better quality trials are still required to confirm with any confidence the true risks and benefits of upright and mobile positions compared with recumbent positions for all women. Based on the current findings, we recommend that women in low-risk labour should be informed of the benefits of upright positions, and encouraged and assisted to assume whatever positions they choose.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16;5:CD002006. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002006.pub3. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Gupta JK1, Hofmeyr GJ, Shehmar M. PMID: 22592681

...OBJECTIVES: To assess the benefits and risks of the use of different positions during the second stage of labour (i.e. from full dilatation of the uterine cervix)...MAIN RESULTS: Results should be interpreted with caution as the methodological quality of the 22 included trials (7280 women) was variable. In all women studied (primigravid and multigravid) there was a non-significant reduction in duration of second stage in the upright group...a significant reduction in assisted deliveries...a reduction in episiotomies ...an increase in second degree perineal tears...increased estimated blood loss greater than 500 ml...fewer abnormal fetal heart rate patterns...In primigravid women the use of any upright compared with supine positions was associated with: non-significant reduction in duration of second stage of labour...this reduction was largely due to women allocated to the use of the birth cushion. AUTHORS' CONCLUSIONS: The findings of this review suggest several possible benefits for upright posture in women without epidural, but with the possibility of increased risk of blood loss greater than 500 mL. Until such time as the benefits and risks of various delivery positions are estimated with greater certainty, when methodologically stringent data from trials are available, women should be allowed to make choices about the birth positions in which they might wish to assume for birth of their babies.

That's fascinating. I had no idea that many women arch back at the last moment before birth. I thought I was odd because all three of my homeborn babies were born with me flinging back at the last moment. They were all in water, but if they hadn't been, I might have been flat in my back. Instead I end up in some part-kneel, part crab walk sort of position. Strange, but it works for me. This was a great article. Thank you!!

ReplyDeleteWith both my babies, I labored on my back in water, so I was not technically on my back, I was simply facing up. I know first hand it relieves pressure in the water, but I'm curious to what extent being in that position while also in water affects the pelvis.

ReplyDeleteI wouldn't think it would affect things too much because 1. the water is lessening the effect of gravity, and 2. the sacrum and tailbone are not being compressed into your pelvic outlet.

ReplyDeleteThere might be a bit of a tendency for the baby to stay high or move down more slowly but I wouldn't think it would be a big deal for most.

As always with birth positions, if it works for you and that baby, then it's a fine position. It's only when there's no progress (or very slow progress) that position might need to be looked at more carefully. Obviously, this one worked for you, so no worries.

Arching my back massively with my 2nd baby saved me from a second cesarean. Or a rupture. His head was hung up on my pelvis & hands & knees only got him more stuck. So I flipped over and hung my upper body off the bed to arch as much as I could. Soon after heard the sound of bone on bone *shudder* and he was finally unstuck and able to move down.

ReplyDeleteI am doubly pissed off that my midwife snapped "get your legs apart" (I was in half-squatting, half kneeling position in birth pool) when baby was crowning, having read "Many childbirth educators have observed that the back half of the pelvic outlet in the squatting position actually increases more when the knees are a bit closer together than farther apart" above. I've always thought that left to my own devices it would have been less painful (and it was certainly very painful round the front), and would not have impeded baby at all since I was having a good ejection reflex.

ReplyDeleteI wanted to arch with all my babies and wasn't allowed to. The nurses were physically blocking me from doing so. First baby 3rd degree tear, second baby broke my tailbone, third baby I birthed in a different hospital and was allowed to arch, no tear, no broken bones, and much less pain. Could be that third baby things were just better adapted but I have my doubts.

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately I was forced into the lying down or slightly elevated position for the entire length of each labor. I was strictly forbidden from getting up and had my legs wrenched apart and back by nurses to facilitate birth.

I wish desperately I could have birthed at home instead.

I guess I was lucky with my hospital birth: I was able to move onto hands and knees just before I started pushing. When the nurse tried to make me flip over, I ignored her. When she then complained to the doctor, according to my doula, his response was to rotate his head, think for a second, and then shrug his shoulders and say "it's fine, she's the one pushing the kid out. If she's comfortable, leave her."

ReplyDeleteWhen I gave birth to my 3rd child, I remember lifting my hips--feet on the bed sort of like a "bridge"--and the baby literally popped out! I guess that was the arched back! I was very lucky in that I labored at home and just birthed the babies at the hospital!

ReplyDeleteOh yes ! I was searching birthing in India & came across your blog post . this is a great write up !

ReplyDeleteI birthed 5 of my 6 at home & in positions I instinctively chose . all were squatting /standing except one he was posterior & I got stuck on my back . it was the most painful of all my births ! when squatting or standing I used either a hammock to hand off of under my rams or my partners neck . when I saw a Nature of Things doc on birth in the 80's I saw a brief clip of women in India using a rope . Oh how I wished for a rope like that !

This is a great read. I have been looking online about alternative birthing methods and really want to try giving birth while standing. I don't think it will be possible in a hospital so I might try home birth. I believe we should have a choice in choosing the most comfortable positions for us since we're the one experiencing it.

ReplyDeleteWHAT A GREAT BLOG THANK YOU!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

ReplyDeleteThis post is wonderful! Will send to my clients...so affirming!

ReplyDeleteThis is amazing! You are amazing! I am a historian and my specialty is History of Medicine. My current research is on midwifery. Was I delighted to read your blog! Thank you for a beautiful piece! Keep up the good work.

ReplyDeleteGreat post. Thanks for posting this article! It is full of great information. hydration solutions

ReplyDeletethis needs to be everywhere!

ReplyDelete